by Gertrud U. Rey

Have you ever wondered if you can “mix and match” SARS-CoV-2 vaccines? For example, would it be ok to boost a first dose of the vaccine produced by AstraZeneca with a dose of the vaccine produced by Pfizer/BioNTech? The latest science shows that such a vaccine regimen actually induces a stronger immune response than a regimen consisting of two doses of the same vaccine.

The occasional incidence of thrombosis in people under the age of 60 after receiving an adenovirus-vectored vaccine like the ones made by AstraZeneca and Johnson & Johnson has prompted several European governments to recommend the use of these vaccines only in people over 60. Because many people under 60 had already been vaccinated with a first dose of the AstraZeneca vaccine and still needed a second dose, they had to decide whether they should continue their regimen with another dose of the same vaccine (i.e., a homologous regimen), or receive an mRNA vaccine instead (i.e., a heterologous regimen).

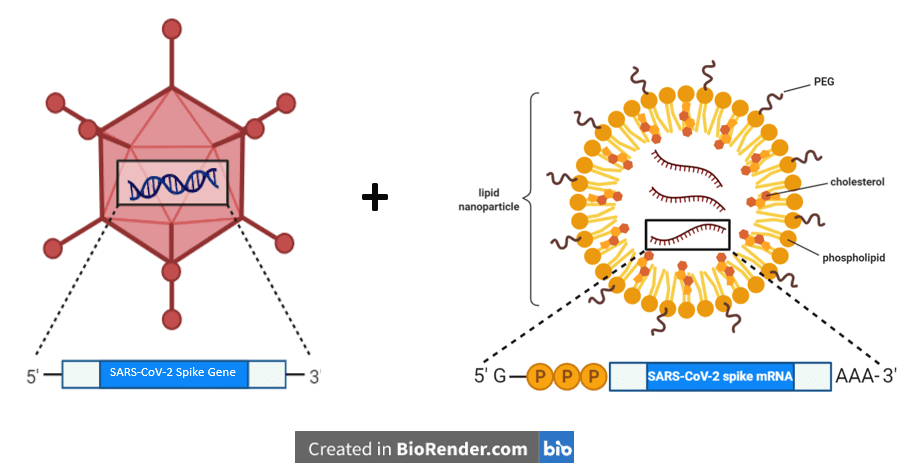

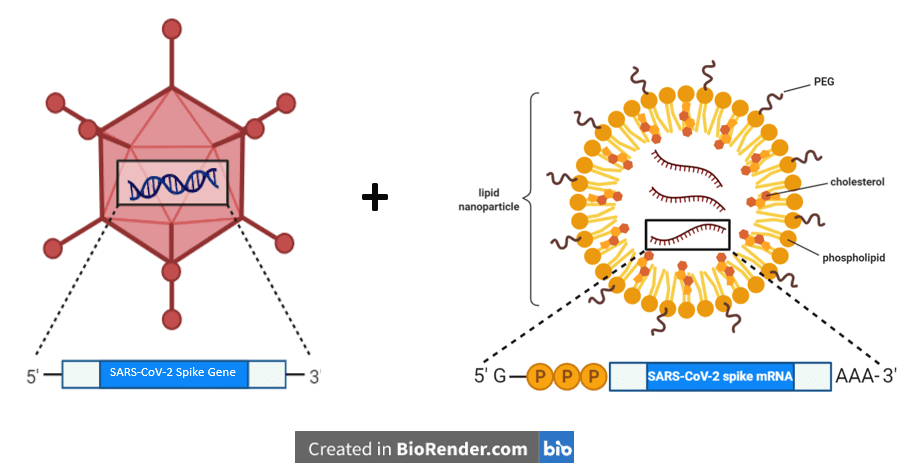

In an effort to evaluate the efficacy of a heterologous SARS-CoV-2 vaccine regimen, the authors of this Brief Communication engaged the participants of an ongoing clinical trial, which aims to monitor the immune responses to SARS-CoV-2 in health care professionals and individuals with potential exposure to SARS-CoV-2. All study participants had already received a first dose of the AstraZeneca vaccine (referred to as “ChAd” in the study) and were given the option of receiving a second dose of the same vaccine or a dose of Pfizer/BioNTech’s mRNA vaccine (referred to as “BNT”). Although both of these vaccines encode the gene for the full-length SARS-CoV-2 spike protein, it is housed slightly differently. In the ChAd vaccine, the spike protein is encoded in an adenovirus vector of chimpanzee origin, while in the BNT vaccine it is surrounded by a lipid nanoparticle.

Out of the 87 individuals who participated in the study, 32 chose a second dose of ChAd and 55 chose to be vaccinated with BNT instead. Participants who chose a homologous ChAd/ChAd regimen received their second dose of ChAd on day 73 after the initial dose and donated a blood sample for analysis 16 days later. Participants who chose a heterologous ChAd/BNT regimen received their dose of BNT 74 days after their initial ChAd dose and donated a blood sample 17 days later. All results obtained from the analyses of the blood samples from these two groups were compared to results obtained from a group of 46 health care professionals who had been vaccinated with two doses of BNT (i.e., a homologous BNT/BNT regimen).

Briefly, the findings were as follows. Relative to the antibody levels induced by the first dose, homologous boosting with ChAd led to a 2.9-fold increase in IgG antibodies against the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein. IgG antibodies are mostly present in the blood and provide the majority of antibody-based immunity against invading pathogens. In contrast, heterologous boosting with BNT led to an 11.5-fold increase in anti-spike IgG, within the range observed in BNT/BNT-vaccinated individuals. A similar pattern was observed with anti-spike IgA antibodies, which are predominantly found in mucus membranes and their fluids. Boosting with BNT induced significantly higher increases in anti-spike IgA than did boosting with ChAd, suggesting that a heterologous boosting regimen induces better antibody responses. Interestingly, although the booster immunization induced an increase in neutralizing (i.e., virus-inactivating) antibodies in both vaccination groups, only heterologous ChAd/BNT vaccination induced antibodies that neutralized all three tested variants (Alpha, Beta, and Gamma), similar to what was observed in BNT/BNT vaccine recipients.

The authors also analyzed the effect of the two different boosting regimens on spike-specific memory B cells, which circulate quiescently in the blood stream and can quickly produce spike-specific antibodies upon a subsequent exposure to SARS-CoV-2. All vaccinees from both the ChAd/ChAd and ChAd/BNT groups produced increased levels of spike-specific memory B cells after receiving their booster shot, with no significant differences observed between the two groups. These results emphasize the importance of booster vaccination for full protection from SARS-CoV-2 infection.

ChAd/BNT recipients also had significantly higher levels of spike-specific CD4+– and CD8+ T cells compared to ChAd/ChAd recipients. CD4+ T cells are a central element of the adaptive immune response, because they activate both antibody-secreting B cells and CD8+ T cells that kill infected target cells. Compared to the ChAd/ChAd regimen, ChAd/BNT vaccination also induced significantly increased levels of T cells that produce spike-specific interferon gamma – a cytokine that inhibits viral replication and activates macrophages, which engulf and digest pathogens. Overall, these results suggest that a heterologous ChAd/BNT regimen induces significantly stronger immune responses than a homologous ChAd/ChAd regimen.

The study did have several limitations. First, it was not a randomized, placebo-controlled trial where each participant was randomly assigned to an experimental group or a control group. Randomizing trial participants eliminates unwanted effects that have nothing to do with the variables being analyzed, so that the only expected differences between the experimental and control groups are the outcome variable studied (efficacy in this case). Subjects in a control group receive a placebo – a substance that has no therapeutic effect, so that one can be sure that the effects observed in the experimental group are real and result from the experimental drug. Second, the authors were unable to test the antibodies for their ability to neutralize the Delta variant, which has recently become the predominantly circulating variant in many parts of the world. Third, the study mostly included young and healthy people, making it difficult to extrapolate the data to other specific patient groups outside of this category. Fourth, the data only show the results of assays performed in vitro, which may not necessarily manifest a clinical significance. Extended studies aimed at determining the practical importance of the observed immune responses are needed to validate the relevance of these responses.

Despite its limitations, the study provides information that could have some valuable practical implications. Most of the currently approved SARS-CoV-2 vaccine regimens involve two doses of the same vaccine. However, access to two doses of the same vaccine may be limited or absent under some circumstances, thus necessitating the use of a different type of vaccine to boost the first dose.

[For a more in-depth discussion of this study, I recommend TWiV 782. The material in this blog post is also covered in episode 24 of Catch This.]

Be nice to know if the reverse order had similar results (i. e. mRNA first, then an adenovirus vaccine).

Pingback: Heterologous Vaccine Regimens Might be Better - Virology Hub

https://www.gov.uk/government/news/most-vulnerable-could-be-offered-booster-covid-19-vaccines-from-september

The UK government is saying it might be giving a third vaccination to everyone over 50. (Not confirmed yet whether this is going to happen or not).

At a guess, the third shot will not be AstraZeneca.

So it looks like we’ll soon have huge numbers of people with 2*AstraZeneca+1*something else (BNT maybe?)