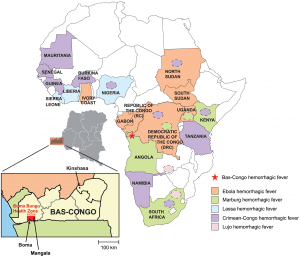

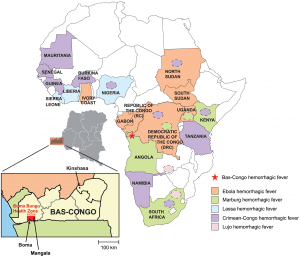

Three cases of hemorrhagic fever that occurred in the spring of 2009 were noteworthy because none of the typical viral suspects could be detected in one patient. Two were young (13, 15 year old) students in the village of Mangala, Bas-Congo province, Democratic Republic of Congo. They lived near each other and went to the same school. Both arrived at the local health center with typical symptoms of hemorrhagic fever, and both died 2-3 days later. The third case was a 32 year old male nurse at the health center who was involved in the care of the other two patients. He developed symptoms of hemorrhagic fever but recovered within a few days.

Deep sequence analysis of RNA extracted from the serum of patient #3 revealed the presence of a novel rhabdovirus, provisionally named Bas-Congo virus (BASV). Phylogenetic analyses reveal that BASV is substantially diverged from the two main human rhabdoviruses, rabies virus and Chandipura virus (ten of the 160 known species of rhabdoviruses have been isolated from humans). BASV is more related to viruses of the Tibrogargan group and the Ephemerovirus genus, which contain arthropod-borne viruses that infect cattle, but clusters separately in an independent branch of the phylogenetic tree.

Antibodies to BASV were detected in the serum of patient #3 and also in the serum of an asymptomatic nurse who had cared for this patient. However, no antibodies to this virus were found in 43 other serum samples from individuals with hemorrhagic fever of unknown origin. These samples came from individuals who lived in 9 of the 11 provinces of the DRC, including Bas-Congo. Nor were antiviral antibodies detected in plasma from 50 random blood donors in one DRC province.

Although the viral genome sequence was determined from RNA extracted from patient serum (where there were 1 million copies per ml of the viral RNA), the virus did not replicate in cell cultures from monkey, rabbit, and mosquito, or in suckling mice. These findings are in contrast to those obtained with a newly discovered coronavirus in humans. It is likely that the samples had not been kept sufficiently cold to maintain viral infectivity. It should be possible to recover virus from a cloned DNA copy of the viral genome.

These data suggest, but do not prove, that BASV caused hemorrhagic fever in the 3 patients. All three cases occurred in a 3 week period within the same small village. BASV nucleic acid and antibodies were detected in the third patient. Given that viruses of the closely related Tibrogargan group and the Ephemerovirus genus are transmitted to cattle by biting midges, it is possible that the initial infections were transmitted by such an arthropod vector. Human to human transmission of the virus could have taken place when the nurse was infected by one or both pediatric patients. However, it should be noted that infection with BASV was not confirmed in either of the first two cases as no clinical samples were available. Other etiologies for this outbreak of hemorrhagic fever should not be ruled out.

Rhabdoviruses are known to cause encephalitis, vesicular stomatitis, or flu-like illness in humans, not hemorrhagic fevers. But these viruses clearly have the potential to cause this disease: members of the Novirhabdovirus genus cause hemorrhagic septicemia in fish. As long as there are viruses to discover, any rules we make about them should be considered breakable.

G Gerard, JN Fair, D Lee, E Silkas, I Steffen, J Muyembe, T Sittler, N Veerarghavan, J Ruby, C Wang, M Makuwa, P Mulembakani, R Tesh, J Mazet, A Rimoin, T Taylor, B Schneider, G Simmons, E Delwart, N Wolfe, C Chiu, E Leroy. 2012. A novel rhabdovirus associated with acute hemorrhagic fever in central Africa. PLoS Pathogens 8.

it means is this virus not Rhabdovirus its a new evolution of dis viral specie ….

As long as humans live, in overpopulation particularly, nature will never be done trying to cull our numbers. Viruses will change, mutate, new ones will appear. It’s a fact I’ve come to accept, and would not be at all surprised if a lethal pandemic pops up in my lifetime.

how bunya virridae can be its causal agent? although bunyaviridae is a plant virusand to my knowledge plants viruses cant infect humans…………..??????

Different members of the Bunyaviridae infect plants and vertebrates. In this case the causative agent of hemorrhagic fever is a rhabdovirus, not a bunyavirus.

This virus is a rhabdovirus. its just that until above instance viruses belonging to the rhabdoviridae family have not been known to cause hemorrhagic fever.