Why would we even consider that a prior dengue virus infection would increase the severity of a Zika virus infection? The first time you are infected with dengue virus, you are likely to have a mild disease involving fever and joint pain, from which you recover and develop immunity to the virus. However, there are four serotypes dengue virus, and infection with one serotype does not provide protection against infection with the other three. If you are later infected with a different dengue virus serotype, you may even experience more severe dengue disease involving hemorrhagic fever and shock syndrome.

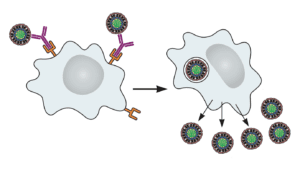

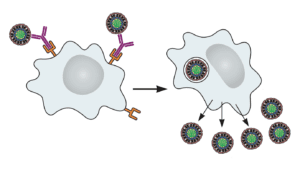

The exacerbation of dengue virus disease has been documented in people. Upon infection with a different serotype, antibodies are produced against the previous dengue virus encountered. These antibodies bind the new dengue virus but cannot block infection. Dengue virus then enters and replicates in cells that it does not normally infect, such as macrophages. Entry occurs when Fc receptors on the cell surface bind antibody that is attached to virus particles (illustrated). The result is higher levels of virus replication and more severe disease. This phenomenon is called antibody-dependent enhancement, or ADE.

When Zika virus emerged in epidemic form, it was associated with microcephaly and Guillain-Barré syndrome, diseases that had not been previously known to be caused by infection with this virus. As Zika virus and dengue virus are closely related, because ADE was known to occur with dengue virus, and both viruses often co-circulated, it was proposed that antibodies to dengue virus might exacerbate Zika virus disease.

It has been clearly shown by several groups that antibodes to dengue virus can enhance Zika virus infection of cells in culture. Specifically, adding dengue virus antibodies to Zika virus allows it to infect cells that bear receptors for antibodies – called Fc receptors. Without Fc receptors, the Zika virus plus dengue antibodies cannot infect these cells. ADE in cultured cells has been reported by a number of groups; the first was discussed here when it appeared on bioRxiv.

The important question is whether antibodies to dengue virus enhance Zika virus disease in animals, and there the results are mixed. In one experiment, mice were injected with serum from people who had recovered from dengue virus infection, followed by challenge with Zika virus. These sera, which cause ADE of Zika virus in cultured cells, led to increased fever, viral loads, and death of mice.

These finding were not replicated in two independent studies conducted in rhesus macaques (paper one, paper two). In these experiments, the macaques were first infected with dengue virus, and shown to mount an antibody response to that virus. Over one year later the animals were infected with Zika virus (the long time interval was used because in humans dengue ADE is observed mainly with second infections 12 months or more after a primary infection). Both groups concluded that prior dengue virus immunity did not lead to more severe Zika virus disease.

Which animals are giving us the right answer, mice or monkeys? It should be noted that the mouse study utilized an immunodeficient strain lacking a key component of innate immunity. As the authors of paper one concluded, it’s probably not a good idea to use immune deficient mice to understand the pathogenesis of Zika virus infection of people.

When it comes to viral pathogenesis, we know that mice lie; but we also realize that monkeys exaggerate. Therefore we should be cautious in concluding from the studies on nonhuman primates that dengue virus antibodies do not enhance Zika virus pathogenesis.

The answer to the question of whether dengue antibodies cause Zika virus ADE will no doubt come from carefully designed epidemiological studies to determine if Zika virus pathogenesis differs depending on whether the host has been previously infected with dengue virus. Such studies have not yet been done*.

You might wonder about the significance of dengue virus antibodies enhancing infection of cells in culture with Zika virus. An answer is provided by the authors of paper one:

In vitro ADE assays using laboratory cell lines are notoriously promiscuoius and demonstrate no correlation with disease risk. For example, DENV-immune sera will enhance even the homotypic serotype responsible for a past infection in the serum is diluted to sub-neutralizing concentrations.

The conundrum of whether ADE is a contributor to Zika virus pathogeneis is an example of putting the cart before the horse. For dengue virus, we obtained clear evidence of ADE in people before experiments were done in animals. For Zika virus, we don’t have the epidemiological evidence in humans, and therefore interpreting the animals results are problematic.

*Update 8/12/17: A study has been published on Zika viremia and cytokine levels in patients previously infected with dengue virus. The authors find no evidence of ADE in patients with acute Zika virus infection who had previously been exposed to dengue virus. However the study might not have been sufficiently powered to detect ADE.

The persnickety thing about these Macaque studies is that they were done using sequential infections.

At first glance, you might think this is a home run: it’s essential for any high impact study into this question to first infect with Dengue and then challenge with Zika. But much like the oft-repeated words of your PhD advisor “mice are not men,” monkeys are also not men! It doesn’t match how DENV-DENV enhancement was first observed in macaques!

All of these studies are investigating whether or not anti-DENV immunity can enhance ZIKV, but they aren’t following the experimental design that showed the gold standard of DENV enhancing DENV!

In the seminal set of rhesus macaque studies published by Halstead et al (1973), they found that primary infection with any of the four DENV serotypes followed by subsequent infection with DENV-1 or DENV-4 a year later actually caused partial protection (reduced viremia and better HAIs). This is in contrast to subsequent infection with DENV-2, which is where they first saw enhancement (1) (2). Muddying the waters further is that studies done in the closely related cynomolgus macaque showed only cross-protection, no enhancement (3).

The final straw that broke the camels back of ADE in macaques, the definitive piece of evidence that showed the macaque model was useful for enhancement studies was *intake of breath* a passive transfer of human sera! (4)

Passive transfer studies are so much better for assessing ADE because A) it shows clearly the polyclonal antibody response dependent mechanism, B) it allows for titration of the antibody response to be perfectly within the window of enhancement and outside of the window of protection, and C) because it avoids the problems of heterogeneity of immune response!

If I have 10 macaques that are outbred (as all experimental macaques are) and injected each with a virus once, and then subsequently re-injected with a secondary challenge virus, I’m opening myself up to 20 separate incidences of immune responses that have to work correctly. If I (and 9 of my friends) get infected with DENV-1, and I pool our sera together, and then inject THAT pooled sera into macaques in the right titration followed by subsequent infection with DENV or ZIKV, then I’ve hedged my bets against some of that inherent biovariability!

Until someone A) does passive transfer of anti-DENV sera in macaques followed by ZIKV infection showing no enhancement or B) shows me clear evidence of primary – secondary infection enhancement from DENV – DENV side by side with DENV – ZIKV, I don’t think there’s any reason to believe these macaque models.

(1) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4196288

(2) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4198024

(3) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17560694

(4) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/117061

The persnickety thing about these Macaque studies is that they were done using sequential infections.

At first glance, you might think this is a home run: it must be essential for any study about ADE in animals to first infect with Dengue and then challenge with Zika, right?

Not so fast. Much like the oft-repeated words of Dr. Peter Palese “mice are not men,†monkeys are also not men! You can’t do infection of DENV then ZIKV in Macaques and say it’s the best test of ADE. It doesn’t match how DENV-DENV enhancement was first confirmed in macaques!

All of these studies are investigating whether or not anti-DENV immunity can enhance ZIKV, but they aren’t following the experimental design that showed the gold standard of DENV enhancing DENV.

In the seminal set of rhesus macaque studies published by Halstead et al (1973), they found that primary infection with any of the four DENV serotypes followed by subsequent infection with DENV-1 or DENV-4 a year later actually caused partial protection (reduced viremia and better HAIs). This is in contrast to subsequent infection with DENV-2, which is where they first saw enhancement (1) (2). Muddying the waters further is that studies done in the closely related cynomolgus macaque showed only cross-protection, no enhancement (3).

If this method of testing ADE (serial infections in rhesus macaques) fails to show DENV – DENV enhancement (a comparably well characterized and understood clinical phenomena), how can we expect it to show enhancement in DENV – ZIKV?

The final straw that broke the camels back of ADE in macaques, the definitive piece of evidence that showed the macaque model was useful for enhancement studies was (*intake of breath*) a passive transfer of human sera (4).

Passive transfer studies are, in my opinion, so much better for assessing ADE* because A) it shows clearly the polyclonal antibody response dependent mechanism, B) it allows for titration of the antibody response to be perfectly within the window of enhancement and outside of the window of protection, and C) because it avoids the problems of heterogeneity of immune response.

*Disclaimer: I was a co-first author on the STAT2 KO mouse study that used passive transfers.

If I have 10 (outbred) macaques and I inject each with a virus once, and then subsequently re-injected with a secondary challenge virus, I’m opening myself up to 20 separate incidences of immune responses that have to work correctly.

If I (and 9 of my friends) get infected with DENV-1, and I pool our sera together, and then inject THAT pooled sera into macaques in the right titration followed by subsequent infection with DENV or ZIKV, then I’ve hedged my bets against some of that inherent biovariability!

Until someone A) does passive transfer of anti-DENV sera in macaques followed by ZIKV infection showing no enhancement (with large n) or B) shows clear evidence of primary – secondary infection enhancement from DENV – DENV side by side with no enhancement from DENV – ZIKV, I don’t think there’s a good reason to believe these macaque models track directly with human disease.

And ultimately yes this question will be solved by epidemiological studies and clinical research! I think we’ll be seeing quite a few more of this type of paper come out in the near future…

(1) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4196288

(2) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/4198024

(3) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17560694

(4) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/117061