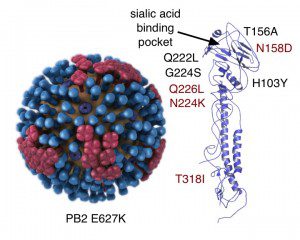

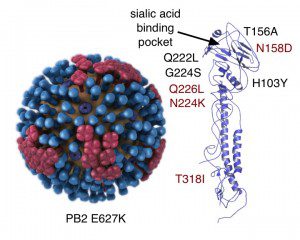

The authors modified the HA protein of an Indonesian strain of influenza H5N1 virus so that it could attach to cell receptors in the ferret respiratory tract. They also added a change in one of the subunits of the viral RNA polymerase, called PB2 protein, that improves replication in mammalian cells (E627K). This H5N1 virus, with the amino acid changes HA Q222L, G224S and PB2 E627K, did not transmit through the air among ferrets.

In an attempt to select a virus with airborne transmissibility, the authors passed their modified H5N1 virus in ferrets. They inoculated a ferret intranasally with virus, waited 4 days, harvested virus from the respiratory tract, and infected the next animal. After ten ferret-to-ferret passages, the pool of viruses produced by the last animal contained mutations in all but one of the 8 viral RNA segments. The original alterations were present (HA Q222L and G224S, PB2 E627K) together with a new change in the HA protein, T156A. This amino acid change prevents the addition of a sugar group to the protein near the receptor binding site, thereby increasing virus binding to mammalian cell receptors.

After ten ferret to ferret passages, the modified H5N1 virus could transmit from one animal to another housed in neighboring cages, e.g. by the aerosol route. All viruses acquired by ferrets by this route had five amino acid changes in common: the original three introduced by mutagenesis (HA Q222L and G224S, PB2 E627K) and two selected in ferrets, HA H103Y and T156A.

The modified H5N1 virus does not transmit with high efficiency among ferrets, and it is not lethal when acquired by aerosol transmission. For this reason, and because we do not know if the virus would transmit among humans, it would not be an effective biological weapon.

A minimum of five amino acid changes in H5N1 virus are required for aerosol transmission among ferrets. This conclusion is based on the observation that the viruses acquired by ferrets through aerosol infection all had five amino acid changes in common. The actual number could be higher. For example, one virus that was studied in more detail differed from the parent H5N1 virus by nine amino acid changes, and other mutations were identified in other isolates. Determining the exact number will require introducing mutations in various combinations into H5N1 virus and testing transmission in ferrets. At present these experiments cannot be because there is a moratorium on H5N1 transmission research.

How do these results compare with those of Kawaoka and colleagues? Those authors found that five amino acid changes in the H5 HA are needed for airborne transmission among ferrets. However, they used a different virus, the 2009 H1N1 pandemic virus with an H5 HA protein. The latter was modified so it could recognize mammalian receptors. They found that amino acid changes that shift the HA from avian to human receptor specificity reduce the stability of the virus. The amino acid changes HA N158D and T318I, which were selected during infection of ferrets, restore stability. The T318I change is near the HA fusion peptide, distant from the receptor binding site. [In the figure, changes identified by Kawaoka and colleagues are in red; black are those identified by Fouchier and colleagues].

It is quite possible that both Kawaoka and Fouchier independently found that virion stability is an important property of viruses that can be transmitted through the air among ferrets. I wonder if Fouchier’s alterations to the HA, Q222L and G224S, destabilized the protein, like those introduced by Kawaoka. This possibility is suggested by the presence of the HA T318I amino acid change that was selected in ferrets. Amino acid 156 is in the HA trimer interface and could confer stability to the protein (the viral HA protein is composed of three copies of one polypeptide; the interface of these three proteins determines its stability). It is an hypothesis that can be easily tested (even with the moratorium on H5N1 transmission research).

The results demonstrate that 5 to 9 amino acid changes are sufficient to allow influenza H5N1 virus to transmit by the aerosol route among ferrets. The findings provide no information about aerosol transmissibility of H5N1 virus in humans. We cannot conclude from this work that a similar number of changes in H5N1 virus will allow transmission among humans. That information can only come from the study of a pandemic H5N1 strain (should such a virus ever emerge).

There is a great deal of good science in this paper, and I cannot imagine hiding it in a vault, or only providing it to certain individuals. I find the findings intriguing, and I am sure that other virologists will be similarly fascinated. One of them might do a seminal experiment on H5N1 transmission as a consequence. But that would never happen if the paper were not published.

The new manuscript is very different from the version submitted in 2011. That paper, in typical Science article style, contained only one paragraph of background information. The experimental findings are described tersely and with little explanation. In contrast, the first five pages of the revised manuscript read like a review article, with substantial detail on influenza virus biology, host range, and the precautions taken during conduct of the experiments. The experimental results are carefully explained. The style is considered and soothing, in contrast with the stark presentation of the original manuscript. I now understand why the NSABB changed their mind and decided to publish this version.

What’s also interesting is that Science swaddled this paper in a whole special section of additional commentary.Â

There are articles about the policy, law, and ethics of working on this

virus, along with a separate modeling study looking at the potential for

a natural H5N1 outbreak. The journal also held a big press conference

about the new work yesterday. I wasn’t able to attend, but speakers

included Anthony Fauci, Bruce Alberts, and a representative from

Novartis Vaccines in addition to the study authors. They’re clearly

trying to undo some of the damage the NSABB fiasco caused to virology’s

public image. I hope it works.

Do you really think that is the goal of all the additional commentary? Personally I think it’s to capitalize on the attention and get more page views. And the accompanying modeling paper is not of much value.

Pingback: Unleashing the Ferrets of Fear | Alan Dove, Ph.D.

Alan, on your blog posting “Unleashing the Ferrets of Fear” (1) you refer to ‘bad reporting’ on the controversial bird flu research topic, and provide an example in an article in the UK Telegraph which reports: “A bird flu pandemic may be close to being a real threat after scientists discovered the virus is already just “three mutations” away from evolving into a strain which would be able to pass from human to human.”(2)

You describe The Telegraph’s article as “rhetorical vomit”, and suggest “there’s a lot of it in the world, from political bumper stickers to fear-mongering headlines”.

On the subject of “fear-mongering headlines”, a blog on the Scientific American website, published on 30 December last year and titled “What really happened in Malta this September when contagious bird flu was first announced”, discusses Ron Fouchier’s presentation at the European Scientific Working group in Influenza (ESWI) meeting in September 2011, when Fouchier is reported to have said his team “mutated the hell out of H5N1” in an effort to make it more transmissible, and warned that “this is a very dangerous virus”. According to Katherine Harmon’s report, Fouchier “advocates that the findings have an important power to “send out the message that H5N1 could become airborne”…And that knowledge should spur scientists and policy makers alike to work harder to develop better vaccines and try to eradicate it in the wild.”(3)

Professor Racaniello has provided a summary (above) of Fouchier’s now published controversial paper. It appears “the modified H5N1 virus does not transmit with high efficiency among ferrets, and it is not lethal when acquired by aerosol transmission…The results demonstrate that 5 to 9 amino acid changes are sufficient to allow influenza H5N1 virus to transmit by the aerosol route among ferrets. The findings provide no information about aerosol transmissibility of H5N1 virus in humans. We cannot conclude from this work that a similar number of changes in H5N1 virus will allow transmission among humans. That information can only come from the study of a pandemic H5N1 strain (should such a virus ever emerge).”

Alan, bearing in mind Professor Racaniello’s summary of Fouchier’s paper, what is your opinion of Fouchier’s melodramatic performance at the ESWI meeting last year?

*For information, I forwarded an open letter to the NSABB re the political and ethical implications of lethal virus development on 31 January 2012. The open letter can be accessed via this link:Â http://bit.ly/AfyAtQÂ

References:

1. “Unleashing the Ferrets of Fear” (posted on 2012.06.22):Â http://alandove.com/content/

2. “Bird flu pandemic just “three mutations” away, scientists show”:Â http://www.telegraph.co.uk/health/healthnews/9348581/Bird-flu-pandemic-just-three-mutations-away-scientists-show.html

3. “What really happened in Malta this September when contagious bird flu was first announced”:Â http://blogs.scientificamerican.com/observations/2011/12/30/what-really-happened-in-malta-this-september-when-contagious-bird-flu-was-first-announced/Â

I was over in Erasmus MC last week and judging by the amount of champagne and beer consumed on Friday night I think they are very glad this paper is now finally out!

Pingback: Origin of the H5N1 storm

Pingback: End of moratorium on influenza H5N1 research

Pingback: Headline writers: Please take a virology course

Pingback: Harvard University: Great virology, bad science writing

Pingback: Incidence of asymptomatic human influenza A(H5N1) virus infection

Pingback: Reconstruction of 1918-like avian influenza virus stirs concern over gain of function experiments

Pingback: What we are not afraid to say about Ebola virus