Absence of XMRV and Closely Related Viruses in Primary Prostate Cancer Tissues Used to Derive the XMRV-Infected Cell Line 22Rv1. The human cell line 22Rv1, which was established from a human prostate tumor (CWR22), produces infectious XMRV. It was previously shown that DNA from various passages of the prostate tumor in nude mice (called xenografts), did not contain XMRV, but cells from the mice do contain two related proviruses called PreXMRV-1 and PreXMRV-2 which recombined to form XMRV between 1993-1996. In a new study samples of the original prostate tumor CWR22 were examined for the presence of XMRV or related viruses. PCR assays targeting the viral gag, pol, and env sequences failed to provide evidence of XMRV in CWR22 tissue. These assays could detect endogenous murine leukemia virus DNA in mouse DNA, indicating that the CWR22 tumor contained neither XMRV nor related viruses. In addition, no XMRV sequences were detected when sections from the CWR22 tumor were examined by in situ hybridization. The same assay previously detected XMRV sequences in stromal cells of prostate tumors. The authors conclude that €œOur findings conclusively show an absence of XMRV or related viruses in prostate of patient CWR22, thereby strongly supporting a mouse origin of XMRV.€

An important question not addressed by this study is why XMRV was originally detected in multiple prostate tumors obtained from patients at the Cleveland Clinic. The authors seem to be working on this problem, as they state that €œ…the sequence of XMRV present in 22Rv1 cells is virtually identical with XMRV cloned using human prostate samples, thus suggesting laboratory contamination with XMRV nucleic acid from 22Rv1 cells as the source. Further experiments designed to confirm or refute this hypothesis are currently underway.€

No biological evidence of XMRV in blood or prostatic fluid from prostate cancer patients. Samples from individuals with prostate cancer were tested for the presence of infectious XMRV and for antibodies against the virus. Neither infectious virus nor antibodies were detected in blood plasma (n = 29) or prostate secretions (n = 5). Among these were five specimens that had previously tested positive for XMRV DNA, including two from the original study. The authors conclude that the results €œsupport the conclusion from other studies that XMRV has not entered the human population€.

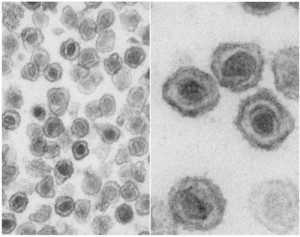

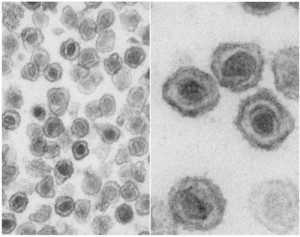

Susceptibility of human lymphoid tissue cultured ex vivo to Xenotropic murine leukemia virus-related virus (XMRV) infection. Although XMRV is not known to cause human disease, whether it has to potential to do so is unknown. The virus can infect a variety of cultured human cells including peripheral blood mononuclear cells and neuronal cells. In this study the authors placed human tonsillar tissue in culture and infected it with XMRV. Proviral (integrated) DNA could be detected in the cells several weeks after infection and virus particles were released into the medium. However these released viruses could not infect fresh tonsillar tissue, possibly due to modification by innate antiviral restriction factors such as APOBEC, which is known to inhibit XMRV infectivity.

Based on their findings the authors conclude that €œlaboratories working with XMRV producing cell lines should be aware of the potential biohazard risk of working with this replication-competent retrovirus€.

It is clear that XMRV does not cause chronic fatigue syndrome; the original findings of Lombardi and colleagues linking the virus to this disease have been retracted by the journal. However there are still two papers in the literature that report the presence of XMRV in prostate – the original XMRV discovery paper and one from Ila Singh’s laboratory. In both papers XMRV detection in tissues was accomplished by using serological procedures. Based on the papers summarized here, the assays did not detect XMRV – but a satisfactory explanation for the positive signals has not yet been provided.

Comments are closed.