A search of the human genome sequence revealed DNA copies of the bornaviral N protein gene. This 370 amino acid viral protein is wrapped around the viral RNA, where it functions during RNA synthesis. Four different insertions of N protein DNA were found, all encoding proteins that are shorter than the viral counterpart. DNA encoding bornaviral N protein was also found in the genomes of the chimpanzee, gorilla, orangutan, rhesus macaque, lemur, Garnett’s galago, African elephant, Cape hyrax, rat, mouse, guinea pig, ground squirrel, little brown bat, and opossum.

The bornaviral RNA genome is not known to be copied into DNA at any stage of the viral replication cycle. Among viruses with RNA genomes, only the retroviruses are known to slip their genetic information into chromosomal DNA. They do so by producing a DNA copy of their RNA genome by using a viral enzyme called reverse transcriptase. The viral DNA then integrates into the host€™s genome, becoming a permanent part of the cell.

These events have no counterparts during replication of bornaviruses. The RNA genomes of these viruses are copied via an RNA intermediate. Yet when cultured cells are infected with bornavirus, a DNA copy of the viral genome can be detected. Based on the sequence of the integrated bornavirus DNA, it seems likely that the N protein mRNA was copied by the reverse transcriptase activity encoded by retrotransposons such as long interspersed nucleotide elements (LINEs). Retrotransposons are sequences related to retroviruses that are found in the genome of many organisms. They may be retroviral progenitors, or degenerate forms of these viruses. Retrotransposons are amazingly abundant: they comprise 42% of the human genome.

How did bornavirus DNA enter the mammalian genome? In cells infected with bornavirus, viral mRNA encoding the N protein was probably copied by cellular reverse transcriptase into DNA. The bornaviral N protein DNA then integrated into the host genome. Of course, in order for viral DNA to become stably integrated into chromosomal DNA, the cell must not be killed by viral infection. The bornavirus infectious cycle is consistent with becoming a permanent part of the cell: infection is not cytolytic, and leads to a persistent infection during which small amounts of virus are produced.

One of the most amazing implications of this finding is that RNA viruses are very, very old. The results of phylogenetic analyses of the bornaviral N DNAs in different mammalian species suggest that bornaviruses have co-existed with primates for at least 40 million years. Only retroviruses were previously known to have existed millions of years ago. This is an important finding because other predictions about the origins of RNA viruses – based on a ‘molecular clock’ with an average rate of nucleotide substitutions per year – have suggested that RNA viruses originated only about 50,000 years ago.

Perhaps the most intriguing question is the role of endogenous viral elements in the mammalian chromosome. It was previously known that 8% of the human genome is made up of endogenous retroviruses, and the human LINE-1 retrotransposon comprises 20% of human DNA. In my view, such sequences must have a functional role, or they would not have been maintained in the genome for millions of years. They are known to affect the human genome by causing insertion mutations and genomic instability, and by altering gene expression. However, many believe that genomes contain nonessential ‘junk’ DNA of no consequence.

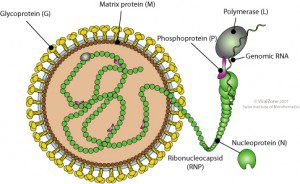

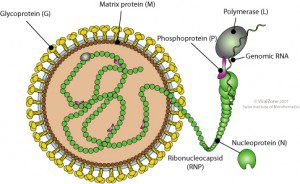

Bornaviruses are agents of a neurological disease of farm horses. The name originates from Borna, Germany, where outbreaks of the disease occurred in 1885. The virus also causes disease in sheep and more rarely in cattle, goats, rabbits, and dogs. The results of serological surveys indicate that humans are infected with bornavirus, but the clinical consequences are controversial. Infection with bornavirus has been associated with neuropsychiatric disorders such as schizophrenia, as well as chronic fatigue syndrome, multiple sclerosis, and motor neuron disease. The association with human disease is consistent with the observation that experimentally infected animals display behavior reminiscent of human neuropsychiatric disorders.

Although I am astounded by these findings, I should not have been surprised. DNA copies of the arenavirus RNA genome have also been found integrated into the chromosomal DNA of infected cells, an observation we discussed one year ago.

Horie, M., Honda, T., Suzuki, Y., Kobayashi, Y., Daito, T., Oshida, T., Ikuta, K., Jern, P., Gojobori, T., Coffin, J., & Tomonaga, K. (2010). Endogenous non-retroviral RNA virus elements in mammalian genomes Nature, 463 (7277), 84-87 DOI: 10.1038/nature08695

“Perhaps the most intriguing question is the role of endogenous viral elements in the mammalian chromosome. It was previously known that 8% of the human genome is made up of endogenous retroviruses, and the human LINE-1 retrotransposon comprises 20% of human DNA. In my view, such sequences must have a functional role, or they would not have been maintained in the genome for millions of years. They are known to affect the human genome by causing insertion mutations and genomic instability, and by altering gene expression.”

You don't actually have to invoke functional roles for the bulk of LINE-1 element insertions in the human genome to explain their presence. As selfish DNA they encode the ability to replicate themselves and create new insertions, although most of the LINE-1 elements in the human genome are inactive due to mutations in their open reading frames or are truncated due to their particular mechanism of insertion. Most of the elements can't actually move anymore and a great deal of them are probably selectively neutral at the level of the host genome and therefore there is little impetus for natural selection to remove them. So they just sit and accumulate mutations.

Some LINE-1 insertions may have become useful to the host, a process known as exaptation. For instance, close to 79% of all human genes contain at least a partial LINE-1 insertion, most of which are in introns. It was found a few years ago that the presence of these insertions might modulate the transcription of certain genes, because the transcriptional machinery seems to recognize LINE-1 sequence and slow down or stop transcription prematurely. Highly expressed genes were found to have less LINE-1 insertions and more lowly expressed genes were often found to have far more. These insertions occurred due to the selfish nature of LINE-1 elements but they may have been retained where they are because at that particular spot they are useful to the host. It doesn't mean that other LINE-1 elements aren't selfish or junk DNA, it just means these particular insertions are useful.

Han, J.S., S.T. Szak, and J.D. Boeke. 2004. Transcriptional disruption by the L1 retrotransposon and implications for mammalian transcriptomes. Nature 429: 268-274.

Nice blog. I haven't read the paper.

Yes I was thinking about this this morning and thinking that viruses probably economize more than cells, thus carry less junk. However, pox genomes carry quite a few broken genes. I don't know the timeline for these, but it's clear that the viruses can carry apparently useless stuff around for quite a while. There's even a poxvirus that has an inserted retrovirus! So as we've already discussed, my prejudice for a long time has been that cells carry a lot of pure junk or broken genes or lame backups or even blank tape.

It's nice to have the borna sequences to give a new date to viruses. I don't understand where the 50,000 year birth date comes from for RNA viruses. Is this a phony number resulting from rapid evolution? I've always figured that viruses and cells have co-evolved from the get-go so that they would be a similar age. Could be viruses even predate cells in the primordial soup.

And is borna (or arena) virus special in doing this or have we just not looked hard enough, as you discuss in TWiV 65? I'll bet that if anyone were to look hard enough they would find evidence for this for just about any virus. I would bet it would maybe be more common for viruses that do an abortive or persistent infection in humans, maximizing the chances of fixing an event. And how do we know that the sequences came from borna and not the other way around? (The paper may address this but as I said I've not read it.)

Cool stuff. TWiV rocks.

As for other viruses – DNA could be in cells as long as they don't kill the cell, obviously. That rules out a lot of RNA viruses including flu. But who knows – maybe in a certain cell type infection is persistent for many acute viruses.

Fifty thousand years comes from calculating back based on the annual rate of change. It's been bothering evolutionary virologists for some time. See this paper for more information on this: http://jvi.asm.org/cgi/content/full/77/7/3893?v…

As for other viruses – DNA could be in cells as long as they don’t kill the cell, obviously. That rules out a lot of RNA viruses including flu. But who knows – maybe in a certain cell type infection is persistent for many acute viruses.

Fifty thousand years comes from calculating back based on the annual rate of change. It’s been bothering evolutionary virologists for some time. See this paper for more information on this: http://jvi.asm.org/cgi/content/full/77/7/3893?view=long&pmid=12634349

Pingback: uberVU - social comments

Pingback: Tweets that mention Bornavirus DNA in the mammalian genome -- Topsy.com

I think it is also important to determine whether the integration sites are the same among different individuals. If so, then we may conclude that it arise from very very ancient time. If not, it would be even more interesting.

Pingback: I'll see your bornaviruses, and raise with a poxvirus | Mystery Rays from Outer Space

Regarding other viral DNA in cells there are two genes, AngRem52 and 104 I believe, that were previously ascribed to the human genome but BLAST searches by two independent virus groups turned up matches to Paramyxoviridae. Both articles discuss where this DNA might have come from:

In silico identification of a putative new paramyxovirus related to the Henipavirus genus.

Schomacker H, Collins PL, Schmidt AC.

Virology. 2004 Dec 5;330(1):178-85.

A novel paramyxovirus?

Basler CF, GarcÃa-Sastre A, Palese P.

Emerg Infect Dis. 2005 Jan;11(1):108-12.

Regarding other viral DNA in cells there are two genes, AngRem52 and 104 I believe, that were previously ascribed to the human genome but BLAST searches by two independent virus groups turned up matches to Paramyxoviridae. Both articles discuss where this DNA might have come from:

In silico identification of a putative new paramyxovirus related to the Henipavirus genus.

Schomacker H, Collins PL, Schmidt AC.

Virology. 2004 Dec 5;330(1):178-85.

A novel paramyxovirus?

Basler CF, GarcÃa-Sastre A, Palese P.

Emerg Infect Dis. 2005 Jan;11(1):108-12.

40M years ago ? I wonder how they determined that.

Would you recognize a virus after 40M years or even 40K years ?

It may change properties like killing cells or even convert from

RNA-virus to retrovirus

The filovirus DNA is integrated into the mouse and rat genome at the

same position. The most likely explanation is that the DNA was

inserted into the evolutionary predecessor of the mouse and rat. Since

this lineage split about 40 million years ago, it provides a minimum

estimate for the age of the integration event at which time the virus

was also present.