by Gertrud U. Rey

Recent news reports have confirmed two cases of Nipah virus infection in West Bengal, India. In response, authorities have quarantined nearly 200 individuals and expanded surveillance efforts both in neighboring countries and among travelers arriving from India. These developments raise an important question: What is Nipah virus, and is it a cause for concern?

Nipah virus was first identified in 1998 in Malaysia, during an outbreak that affected both pigs and humans. The leading hypothesis for its emergence is that the virus spilled over from infected fruit bats to pigs when pig-farming operations expanded into areas inhabited by bats. Pigs exposed to bat‑contaminated material became infected and subsequently transmitted the virus to farmers. This scenario reflects a well‑recognized pattern of zoonotic spillover, in which viruses maintained in wildlife populations cross into humans through intermediate animal hosts. As outlined in an earlier post on the role of bats as reservoirs for high‑risk pathogens, fruit bats can harbor a variety of viruses with the potential to emerge in human populations.

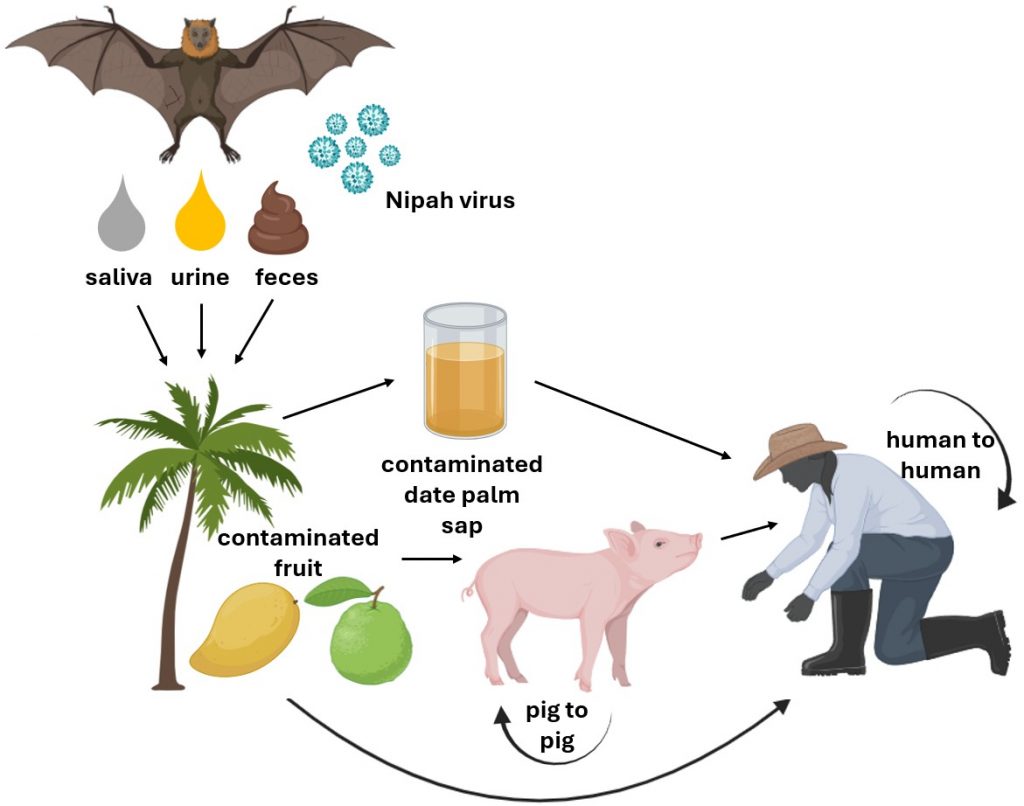

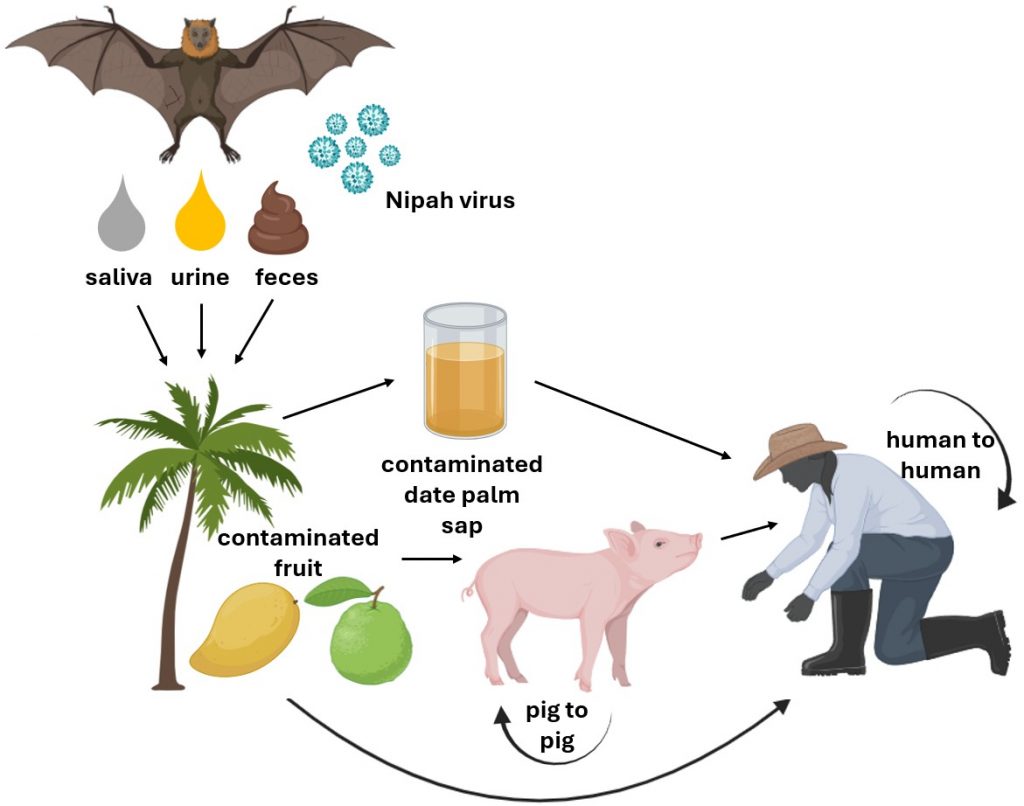

As a member of the Paramyxoviridae family, Nipah virus is related to other clinically important viruses like measles virus, mumps virus, and respiratory syncytial virus (RSV). Nipah virus circulates in fruit bats across Asia, the South Pacific and Australia, especially among species of the Pteropus genus, commonly known as “flying foxes.” These bats shed Nipah virus in their saliva, urine, and feces, thereby contaminating local fruit or palm sap that may subsequently be consumed by humans or by intermediate animal hosts.

Transmission of Nipah virus happens most commonly from animals to humans, through direct contact. Nevertheless, the virus can also spread from one person to another, typically during exposure to the bodily fluids of an infected individual, including respiratory secretions, saliva, or urine. Consumption of fruit or fruit‑derived products contaminated with bat excretions also contributes to transmission. In particular, drinking raw date palm sap carries deep cultural significance in many South Asian communities, yet public awareness of the associated health risks remains limited. Fruit bats frequently contaminate sap collection sites with their saliva, urine, or feces, while feeding on the exposed sap.

Nipah virus particles are encased in a lipid membrane and can have a filamentous or spherical shape generally measuring 120-150 nm in diameter. The viral genome is composed of a single-stranded, negative-sense RNA molecule that is tightly associated with nucleocapsid proteins. Nipah virus infects primarily epithelial cells of the respiratory tract, endothelial cells lining blood vessels, and neurons in the central nervous system. As a result, infection frequently leads to widespread systemic disease, prominently affecting the lungs, kidneys, and brain, and often causing severe respiratory illness and encephalitis. The virus is highly lethal, as demonstrated by a 2011 outbreak in Southeast Asia that resulted in 211 deaths among 280 reported cases – corresponding to a case fatality rate of approximately 75%.

This high fatality rate – combined with the virus’s potential for human‑to‑human transmission and the lack of approved vaccines or targeted treatments, makes Nipah virus a significant public health concern. Furthermore, because increased contact between animal species and humans is a major driver of cross‑species transmission, environmental and ecological changes, particularly those resulting from human encroachment into wildlife habitats, may heighten the likelihood of future spillover events. Therefore, improved strategies for safe agricultural and farming practices that minimize contact between livestock and fruit bats are urgently needed.