Q: Are you aware of efforts to make the virus strain nomenclature more informative? Understanding what segments/genes are related historically and sequence wise to what is confusing using the ‘serological’ definitions like H1N1. What about the other segments? What about subtyping further the HA and NA genes?

A: See the question below which refers to efforts to revise nomenclature for influenza viruses. Serological definitions are still used because it is not possible to infer the antigenic properties of the HA or NA from the nucleotide sequence (see antigenic cartography). There is as yet no compelling reason to subtype further. Other genes are not included in the serological typing because these do not play a major role in generating protective antibodies.

Q: Is there a good way to get a statistical handle on the relative rates if H1N1 isolate detection vs. others currently, particularly co-infection? It will be interesting to see what happens with the flu species population and what the interaction of H1N1 in the background of other species will be.

A: Such information is provided by CDC and WHO; most of us don’t have access to it until it is provided, either on websites or publications such as MMWR or in research journals. There is no question that this is an interesting time to be observing the interaction of three human influenza A subtypes.

Q: Hello, first time poster but I’ve been reading this blog for some time now. This may have been discussed here before but I have a very simple question. The new H1N1 strain – does this represent antigenic drift or shift?

A: What a good question, which no one has asked yet. Let’s look at the textbook definitions. Antigenic shift involves major antigenic changes in which a new HA or NA subtype is introduced into the human population (e.g. H1 to H2). Antigenic drift occurs as a result of point mutations that lead to minor, gradual antigenic changes in HA or NA. Mutations in the HA or NA of human influenza viruses occur at a rate of about 1% per year.

Because the new H1N1 virus does not have a new H/N subtype, it’s not a consequence of antigenic shift. But the new HA is quite different from the HA of last season’s H1N1 virus – at least 117 amino acids, comparing A/Brisbane/59/2007 (H1N1) with A/New York/1669/2009 (H1N1). Clearly the new H1N1 could not have been derived from the previous H1N1 by a few mutations. But it’s still technically drift.

Q: May I ask you if you feel that the CDC is procrastinating on whether to ask vaccine manufacturers to switch over from the seasonal strain to a swine flu vaccine instead? If and when it does, it will take six months for the first batch to be ready, I read. Some makers have said they can produce both but smaller manufacturers say they can only produce one or the other. My question is why can’t they be produced together as one shot? If the current one is trivalent – H1N1, H3N2 and one other, I suppose – why can’t the swine H1N1 also be added into the same shot? Is there a technical (?antigenic) reason this cannot be done?

A: Please listen to my interview with Dr. Peter Palese on twiv.tv. Basically, vaccine production is going forward, in case the new H1N1 strain returns to the northern hemisphere in the fall. There is no biological reason why the vaccine could not be combined with the current trivalent preparation. Obviously keeping the new H1N1 vaccine separate provides flexibility in deciding whether or not to deploy it. If you mix it with the trivalent, the decision cannot be reversed.

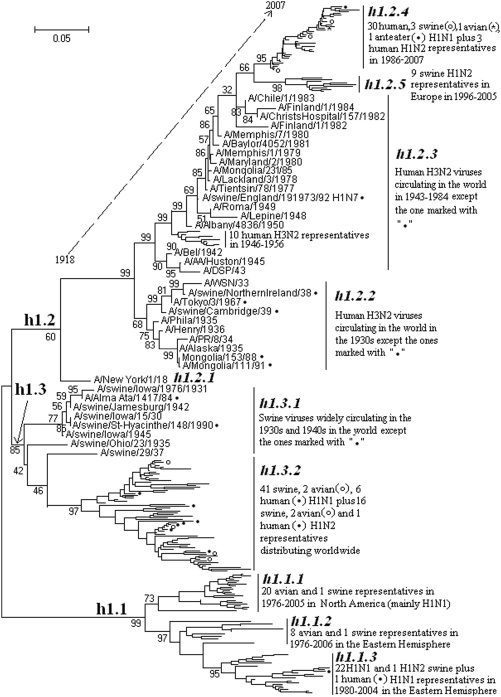

Q: Reading a recent ProMed-Mail about the H1N1 flu virus, I read this ” … There are 3 main clusters of H1 subtype swine influenza viruses circulating in pigs in the world, designated as h1.3.2, h1.1.3 and 1.2.5 by a newly proposed universal numeral nomenclature system for all influenza viruses. They correspond to classical, avian-like and human-like swine influenza viruses, respectively” … could you please provide – but in a simple way – basics of this numeral system for nomenclature for flu viruses ?

A: I believe that the ProMed-Mail post is referring to an analysis of influenza virus sequences published in PLoS ONE. In that paper they compared the sequences of thousands of viruses and constructed phylogenetic trees – a graphical representation of the relationships among the sequences. The tree for H1 hemagglutinins is reproduced below. The new proposed nomenclature consists of a letter indicating h (HA) or n (NA) followed by the subtype; then two other numbers based on the branches of the tree. From the image you can see that h1.1, h1.2, and h1.3 represent the three main branches of the tree. The third digit is based on further branching.

Q: I have been to coastal Mexico a few times in April and it has always been hot and humid. One would think these conditions would make virus transmission difficult, so it’s surprising that this outbreak occurred during March and April. I did a bit of digging and I think I know the answer. Since I’ve heard this come up a few times, it may worth sharing this in you next posting. Mexico City is cooler and drier than coastal areas especially during the winter. March and April are among the driest months, and the nighttime temperature is probably cool enough year round. Here’s a chart.

A: Your theory is certainly plausible. But remember, there were also outbreaks outside of Mexico City (e.g. Veracruz). And the outbreak in Mexico seems to be over; the borders of the ‘season’ can be fuzzy. There are always exceptions to the seasonality rule. For example, influenza outbreaks may occur during the winter in closed communities, presumably by contact.

Q: My second question is about minor differences within a strain. I’ve been using some of the HA sequences for the new H1N1 on genbank as a vehicle for learning bioruby, and have noted a few differences. At what point do the differences become significant? On Futures in Biotech 40, Dr. Palese mentioned that 3-4 amino acid differences in the Hemagglutinin protein could be to enough cause an immunological difference. As an example, there is a 6 base-pair difference which results in a 4 amino acid difference between the California (FJ966082) and New York (FJ969509) HA sequences. Is that unusual? BTW, for perspective, I also compared the California sequence to the 1918 H1N1 HA sequence (AF117241) and found 311 base-pair differences (out of 1701), and 79 amino acid differences (out of 567).

A: It’s very difficult to predict antigenicity from the nucleotide sequence, so we can’t say if those differences are significant with respect to protective immunity. See the following from antigenic cartography:

There is a close relationship between genetic and antigenic change for human influenza A(H3N2) virus, but genetic distance can be an unreliable predictor of antigenic distance. For example, a change in a single amino acid may cause a disproportionately large change in the binding properties of a virus strain.

Q: The one thing that I do not understand is the mechanism by which the growth stops and the case count “peaks”. Can you please enlighten me as to the mechanism that causes this? In other words, what is going to stop this virus from infecting tens of millions of people by mid-June and a hundred million a few days later which is the path that it is currently on? How does it actually “poop out” short of infecting everyone.

A: Outbreaks stop for several reasons, including seasonality, and we’ve talked about that here quite a bit. I expect the reduced transmission of the virus in the northern hemisphere will soon stop spread. A second is population immunity. Transmission of viral infections require a certain level of susceptible individuals, which varies for each virus. As the number of immune individuals grows, the virus cannot effectively be transmitted, and the outbreak stops.

Vincent, you flipped on me – you first said that this was indeed antigenic shift last week. I'm joking of course but it does raise some important questions. For example, now that you've stated that this is in fact drift – are you comfortable in calling this a “novel” influenza strain. Considering the fact that we see drift all the time and do not generally use the term “novel” to describe these point mutations.

Yes, I know I flipped. I'm glad you are keeping track of my answers! A

good scientist must always be willing to revise their position. I

wasn't comfortable with my original answer so I asked Dr. Palese and

he felt that it's not shift because it doesn't involve a change in HA

subtype. But drift is a stretch because, as I wrote in the post, the

HA differs by many more amino acids than one would expect to occur

from one season to another. However, there are certainly drifted

strains of the same subtype many years apart that differ by that much.

So It's drift, albeit an unusual form. The strain is novel, in my

view, because it has a unique combination of RNA segments not seen

before. Briefly: PB2, PB1, PA, HA, NP, NS from viruses infecting North

American pigs; NA and M from viruses infecting Eurasian pigs.

The problem is always is categorizing viruses according to human

terms. In the end, the viruses evolve in their own categories.

I was reading about the 1977 Russian flu pandemic here, http://www.globalsecurity.org/security/ops/hsc-… , and a strong case is made that the 1977 flu was made in the lab. Can you dismiss this out of hand or does this article make a valid point?

The emergence of the 'Russian' strain of H1N1 influenza virus in 1977

was most likely a laboratory accident. I've written a blog post about

this incident (https://virology.ws/2009/03/02/origin-of-cur…).

I was working in the Palese lab when this outbreak occurred and knew

exactly what was going on. The strain was nearly identical to viruses

that circulated in the 1950s. That virus was not made in a lab, but it

was probably released from a lab.

The emergence of the 'Russian' strain of H1N1 influenza virus in 1977

was most likely a laboratory accident. I've written a blog post about

this incident (https://virology.ws/2009/03/02/origin-of-cur…).

I was working in the Palese lab when this outbreak occurred and knew

exactly what was going on. The strain was nearly identical to viruses

that circulated in the 1950s. That virus was not made in a lab, but it

was probably released from a lab.

What does the H and N stand for in H1N1 virus?

H = hemagglutinin, N = neuraminidase. These are the proteins on the

surface of the virus. They are important for the virus ability to

enter and leave cells, and our immune responses are directed against

them. In an earlier post at virology blog there is an illustration of

these.

Thanks for all the great info. You are the best.

Are there any new thoughts on why the virus in the us seems to be killing folks who are relatively young? the last two were a 30 yo man in tx, a woman in her late 40s. a man who is in his mid 50s is on a ventilator in ny. i understand there are theories about 1918 and the “cytokine storm” but are there other ideas too? thanks!

It is far too soon to be speculating. As Palese would say, the numbers

are too small. But it's possible that older people have cross

protective immunity. A paper in PLOS just came out which says that

natural infection generates hetero-subtypic (e.g. H3 infection, H1

protection), but that vaccination with killed vaccine does not.

Therefore, the older people have had more natural infections, hence

cross protection. Younger people have been immunized, no cross

protection.

so – how long after being exposed and/or infected, will you still test positive (via nasopharyngeal swab, or using serological study? If I was sick “then” (a few weeks ago) – can they find any sign of previous infection?

After a week there won't be any more virus in a swab. However the

anti-viral antibodies will be present in serum for at least 10 years.

My mother is in her late 70's and was exposed to a Type B H1Ni when she was 5 or 6 years old as a result, I think, of the 1918 H1N1 “Spanish Influenza's” transmission to pigs during that pandemic. Does she now have a natural immunity to the current strain of “Swine Flu” or H1N1

People born before 1950 have some immunity to the current H1N1 strain

because the virus is similar to those circulating from 1918 until

then. Whether or not your mother has protective antibodies depends

upon whether she was infected with the 1918 strain (or any other

influenza strain until the late 1940s) and whether she developed an

immune response. But she has a better chance of being immune than,

say, those born after 1950.

My mother is in her late 70's and was exposed to a Type B H1N1 when she was 5 or 6 years old as a result, I think, of the 1918 H1N1 “Spanish Influenza's” transmission to pigs during that pandemic. Does she now have a natural immunity to the current strain of “Swine Flu” or H1N1? Obviously I am a not a professional at anything but being a chef so please excuse any ignorance in this matter.

People born before 1950 have some immunity to the current H1N1 strain

because the virus is similar to those circulating from 1918 until

then. Whether or not your mother has protective antibodies depends

upon whether she was infected with the 1918 strain (or any other

influenza strain until the late 1940s) and whether she developed an

immune response. But she has a better chance of being immune than,

say, those born after 1950.

What does the H and N stand for in the FLU names like H1N1 or H1N8? Also I recieved the Flu Shot for the 1st time and I feel muscle aches pains and my head feels weak or loopy is this normal?

According to the cdc and other sources the 2009 novel H1N1 is an antigenic shift. http://www.cdc.gov/h1n1flu/information_h1n1_virus_qa.htm

Earlier you state, that it technically is only an antigenic drift.

I am confused…