Merkel cell carcinoma (MCC) is a relatively rare human skin cancer, although its incidence has increased in the past twenty years from 500 to 1500 cases per year. This cancer occurs more frequently than expected in individuals who are immunosuppressed, such as those who have received organ transplants or who have AIDS. A similar pattern of susceptibility is also observed for Kaposi’s sarcoma, a tumor that is caused by the herpesvirus HHV-8. Therefore it was suggested that MCC might also be caused by an infectious agent.

To identify the etiologic agent of MCC, the nucleotide sequence of total mRNA from several MCC tumors was determined and compared with the sequence of mRNA from a normal human cell. This analysis revealed that the MCC tumors contained a previously unknown polyomavirus which the authors named Merkel cell polyomavirus (MCV or MCPyV). The viral genome was found to be integrated at different sites in human chromosomal DNA from MCC tumors.

If MCV infection causes MCC, then the viral genome should be present in tumors but not in normal tissues. MCC DNA was found in eight of ten MCC tumors, each obtained from a different patient. The viral genome was not detected in various tissues samples from 59 patients without MCC. Furthermore, the viral genome had integrated into one site in the chromosome of one tumor and a metastasis dervied from it. This observation indicates that integration of the viral genome occurs first, before division of the tumor cells.

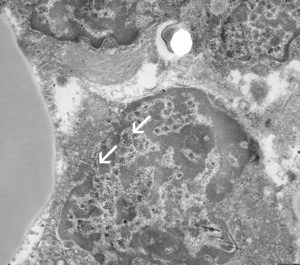

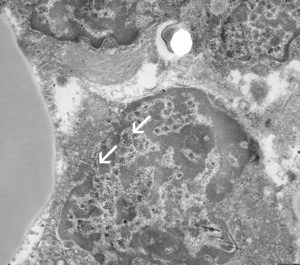

In subsequent studies MCV DNA has been detected in 40-85% of the MCC tumors examined. The viral DNA is not found in small cell lung carcinoma, which, like MCC, is also a neuroendocrine carcinoma. MCV particles have also been detected by electron microscopy in the cytoplasm and nucleus of tumor cells from one patient, suggesting ongoing viral replication.

How might MCV cause Merkel cell carcinoma? Expression of the viral protein known as T antigen might be sufficient to transform cells. Alternatively, integration of the viral DNA into human DNA could lead to unregulated synthesis of a protein that transforms cells. To prove that MCV causes Merkel cell carcinoma, it will be necessary to demonstrate that infection with the virus, or transfection with viral DNA, transforms and immortalizes cells in culture.

Feng, H., Shuda, M., Chang, Y., & Moore, P. (2008). Clonal Integration of a Polyomavirus in Human Merkel Cell Carcinoma Science, 319 (5866), 1096-1100 DOI: 10.1126/science.1152586

Wetzels, C., Hoefnagel, J., Bakkers, J., Dijkman, H., Blokx, W., & Melchers, W. (2009). Ultrastructural Proof of Polyomavirus in Merkel Cell Carcinoma Tumour Cells and Its Absence in Small Cell Carcinoma of the Lung PLoS ONE, 4 (3) DOI: 10.1371/journal.pone.0004958

This is a thoughtful overview of this newly-discovered virus. In terms of molecular measures of causation, I quibble with Dr. Racaniello on whether immortalization of cells by a virus or its DNA is the defining evidence needed to determine if it is a cancer virus. Many viruses and gene fragments can immortalize cells in culture (e.g., the immediate-early region of human CMV) but are not likely to cause human cancer. On the other hand, some cancer-causing genes (e.g., MYC) tend to kill rather than immortalize cells in culture when expressed without complementation (e.g., H-Ras). These assays have been helpful in assessing viral carcinogenicity, they can only be used as rough molecular guides to understanding viral carcinogenesis. They have been used by some scientists as intellectual straight-jackets rather than important but imperfect tools.

Instead, the most telling evidence that a virus causes cancer is human cancer epidemiology itself–as alluded to RYoerge's reference of some of the pioneers in epidemiologic causation. I disagree, however, with most of this comment since there is no substitute for at least casually looking at the primary scientific literature. The evidence is overwhelming that MCV causes ~80% of Merkel cell cancers, a proportion that is similar to the estimated percentage of virus-induced liver cancers. Causation is a normative exercise but rather than restating AB Hill's criteria, or another formalism, I would like to respond to this comment by restating points made in the essay:

1) The virus is monoclonally-integrated into the cancer cells in MCV-positive tumors, as is the case for some high-risk papillomaviruses in cervical cancer (Feng et al, Science 2008; Sastre-Garau et al J Path 2009). This actually already has been discussed in two separate editorials by Harald zur Hausen (Int J Cancer 2008, PNAS 2008: “The positive Merkel cells contain viral DNA in an integrated and clonal form, suggesting an involvement of this virus in the etiology of those tumors.”)

Thus the viral suspect was present at the scene of the crime.

2) Tumor-specific mutations are present in the T antigen of virus from tumors but not from healthy tissues (Shuda et al, PNAS 2008). These mutations may arise from sun-exposure–although this is not known for certain. No intact, unmutated helper viruses have been found in these tumors. These mutations eliminate the ability of the virus to replicate by truncating its helicase and therefore the virus is not a passenger virus. The MCV virions (from Wetzels et al, PLoS One 2009) shown in the electon micrograph picture on this diary are probably empty-capsid, self-assembling virus-like particles from expression of the VP1 gene of integrated MCV rather than replicating and transmissible virus (see Tolstov et al. Int J Cancer 2009). It also remains possible, however, that a minority of tumors retain unintegrated, episomal virus as is the case for some genotypes of HPV in cervical cancer.

Now, the suspect's alibi has been eliminated.

3) Antibody staining specifically for MCV T antigen protein directly shows that the virus is present and expressing this nuclear, RB1-inhibiting oncoprotein in each tumor cell (Shuda et al. Int J Cancer 2009).

The virus had both the means and the motive and the gun is still smokin' in its hands.

RYoerge's comment suggesting that MCV is an poorly-examined human rumor virus does not hold water. The virus has been rigorously examined and I highly respect my colleagues' rapid progress in describing this agent in a little over a year. As of today (May 26, 2009) there are 26 primary data articles on MCV detection in Merkel cell carcinoma in the PubMed database (and almost as many reviews). All 26 primary articles confirm that MCV is found specifically in Merkel cell carcinoma and is generally not found in other cancers by independent tests of DNA hybridization/amplification, in situ immunohistochemistry and serology; none find evidence against this association. To date, there is no data that I am aware of suggesting that the virus is not the cause of most Merkel cell carcinomas.

This is just the beginning phase for studies on this virus and I hope that RYeorge will continue look at this data and give new opinions on it. Whether other diseases and cancers are caused by this virus is unknown, but MCV and Merkel cell carcinoma is already well-trod ground as can be seen in a simple PubMed search.

I cannot agree more with RYoerge's comment that “patience and good science, replicated from lab-to-lab, should be the coin of the realm” as is shown by the published literature on MCV from many laboratories around the world. It's a growing body of literature that I for one am proud to have contributed to. Having survived the Kaposi's sarcoma and KSHV wars (and yes, KSHV does indeed cause KS), I admire skepticism on this subject as long as it does not spill over into tendentious captiousness.

Infection is estimated to cause 20% of the world-wide burden of cancer (Parkin Int J Cancer. 2006 Jun 15;118(12):3030-44) and so it remains vital that virologists continue the rigorous search for viral causes and for cures to infection-related cancers.

Patrick Moore, University of Pittsburgh

This is a thoughtful overview of this newly-discovered virus. In terms of molecular measures of causation, I quibble with Dr. Racaniello on whether immortalization of cells by a virus or its DNA is the defining evidence needed to determine if it is a cancer virus. Many viruses and gene fragments can immortalize cells in culture (e.g., the immediate-early region of human CMV) but are not likely to cause human cancer. On the other hand, some cancer-causing genes (e.g., MYC) tend to kill rather than immortalize cells in culture when expressed without complementation (e.g., H-Ras). These assays have been helpful in assessing viral carcinogenicity, they can only be used as rough molecular guides to understanding viral carcinogenesis. They have been used by some scientists as intellectual straight-jackets rather than important but imperfect tools.

Instead, the most telling evidence that a virus causes cancer is human cancer epidemiology itself–as alluded to RYoerge's reference of some of the pioneers in epidemiologic causation. I disagree, however, with most of this comment since there is no substitute for at least casually looking at the primary scientific literature. The evidence is overwhelming that MCV causes ~80% of Merkel cell cancers, a proportion that is similar to the estimated percentage of virus-induced liver cancers. Causation is a normative exercise but rather than restating AB Hill's criteria, or another formalism, I would like to respond to this comment by restating points made in the essay:

1) The virus is monoclonally-integrated into the cancer cells in MCV-positive tumors, as is the case for some high-risk papillomaviruses in cervical cancer (Feng et al, Science 2008; Sastre-Garau et al J Path 2009). This actually already has been discussed in two separate editorials by Harald zur Hausen (Int J Cancer 2008, PNAS 2008: “The positive Merkel cells contain viral DNA in an integrated and clonal form, suggesting an involvement of this virus in the etiology of those tumors.”)

Thus the viral suspect was present at the scene of the crime.

2) Tumor-specific mutations are present in the T antigen of virus from tumors but not from healthy tissues (Shuda et al, PNAS 2008). These mutations may arise from sun-exposure–although this is not known for certain. No intact, unmutated helper viruses have been found in these tumors. These mutations eliminate the ability of the virus to replicate by truncating its helicase and therefore the virus is not a passenger virus. The MCV virions (from Wetzels et al, PLoS One 2009) shown in the electon micrograph picture on this diary are probably empty-capsid, self-assembling virus-like particles from expression of the VP1 gene of integrated MCV rather than replicating and transmissible virus (see Tolstov et al. Int J Cancer 2009). It also remains possible, however, that a minority of tumors retain unintegrated, episomal virus as is the case for some genotypes of HPV in cervical cancer.

Now, the suspect's alibi has been eliminated.

3) Antibody staining specifically for MCV T antigen protein directly shows that the virus is present and expressing this nuclear, RB1-inhibiting oncoprotein in each tumor cell (Shuda et al. Int J Cancer 2009).

The virus had both the means and the motive and the gun is still smokin' in its hands.

RYoerge's comment suggesting that MCV is an poorly-examined human rumor virus does not hold water. The virus has been rigorously examined and I highly respect my colleagues' rapid progress in describing this agent in a little over a year. As of today (May 26, 2009) there are 26 primary data articles on MCV detection in Merkel cell carcinoma in the PubMed database (and almost as many reviews). All 26 primary articles confirm that MCV is found specifically in Merkel cell carcinoma and is generally not found in other cancers by independent tests of DNA hybridization/amplification, in situ immunohistochemistry and serology; none find evidence against this association. To date, there is no data that I am aware of suggesting that the virus is not the cause of most Merkel cell carcinomas.

This is just the beginning phase for studies on this virus and I hope that RYeorge will continue look at this data and give new opinions on it. Whether other diseases and cancers are caused by this virus is unknown, but MCV and Merkel cell carcinoma is already well-trod ground as can be seen in a simple PubMed search.

I cannot agree more with RYoerge's comment that “patience and good science, replicated from lab-to-lab, should be the coin of the realm” as is shown by the published literature on MCV from many laboratories around the world. It's a growing body of literature that I for one am proud to have contributed to. Having survived the Kaposi's sarcoma and KSHV wars (and yes, KSHV does indeed cause KS), I admire skepticism on this subject as long as it does not spill over into tendentious captiousness.

Infection is estimated to cause 20% of the world-wide burden of cancer (Parkin Int J Cancer. 2006 Jun 15;118(12):3030-44) and so it remains vital that virologists continue the rigorous search for viral causes and for cures to infection-related cancers.

Patrick Moore, University of Pittsburgh