An outbreak of respiratory disease in Ugandan chimpanzees provides insight into how virus infection can shape the genome and lead to differences in the cell receptor gene that regulate susceptibility to infection.

Severe respiratory disease was noted in the Kanyawara community of chimpanzees in western Uganda from February to August of 2013. During this outbreak, 55 animals became ill and 5 died. Deep sequence analysis, and subsequently polymerase chain reaction, of swab samples from one of these chimpanzees revealed the presence of human rhinovirus C45. The closest known relative of this virus was previously obtained in 2000 from a human in the United States.

Rhinovirus C45 was not identified in any other of the chimpanzees that fell ill during this outbreak of respiratory disease. Clinical signs observed are consistent with infections by rhinovirus C, but it is also possible that other viruses were involved. Rhinovirus C was previously thought to infect only humans.

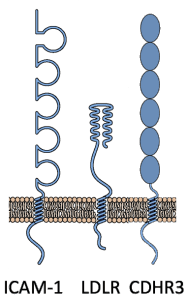

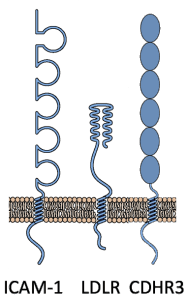

Over 160 distinct rhinovirus genotypes are grouped into types A, B, and C. The latter cause about 50% of all human upper respiratory tract infections, and have been associated with influenza-like symptoms and acute asthma exacerbations in children. A single nucleotide polymorphism in the human gene encoding the HRV C receptor, CDHR3 (cadherin-related family member 3, pictured), is associated with severe disease and asthma. Specifically, a tyrosine at amino acid 529 of CDHR3 causes higher cell surface levels, increased virus binding and virus yields. A cysteine at the same position causes lower surface levels, less virus binding and replication, and less risk of disease.

It is thought that rhinovirus C emerged in human populations about 8,000 years ago at a time when human genomes harbored the Y529 allele. Subsequently the C529 protective allele emerged under selective pressure imposed by viral disease. Consistent with this hypothesis, the genomes of Neanderthal and Denisovan humans contain only the Y529 allele.

Genotyping of DNA from 41 chimpanzee fecal samples collected during the outbreak showed that all are homozygous for CHDR3 529Y, as are 24 chimpanzee genomes from the Great Ape Genome Project. This observation is consistent with the absence of widespread HRV C circulation for thousands of years in chimpanzees, which would be expected to select for the protective 529C allele.

HRV C infection in Ugandan chimpanzees was likely introduced by researchers and tourists who frequent the parks. The virus is common among the humans in sub-Saharan Africa. When visiting chimpanzees, humans should wear facemasks and use hand sanitizer to reduce transmission and protect the endangered chimpanzee communities.

Update 2/6/2019: Excellent article on this outbreak with some backstory and comments from the investigators at UW News: link to article.

Pingback: A human rhinovirus in chimpanzees - Virology

Pingback: A human rhinovirus in chimpanzees - VETMEDICS