A study done in 1985 on a 16th century Italian mummy suggested that the two year old child had smallpox. Recent sequence analysis of tissues from the mummy now reveal the presence of hepatitis B virus, not smallpox virus. The sequence of the viral genome suggests that HBV entered the human population well before 1500.

Technical improvements in high-throughput sequencing and the recovery of DNA from ancient samples have enabled the study of viral genomes from increasingly older samples. The study of ancient DNA (aDNA) not only helps identify the cause of previous outbreaks, but provides insight into viral evolution.

The isolation of aDNA poses difficulties not encountered with contemporary samples. One problem is that old DNA tends to be damaged. Another is that contamination with modern DNA can render an entire study useless. Consequently, aDNA must be extracted from specimens in clean facilities dedicated entirely to studying ancient specimens. Verifying that aDNA is actually old, and not a contaminant, is an important part of such studies, but certain types of DNA damage can actually help in this analysis.

Over time, DNA tends to undergo deamination – the loss removal of an amine from the bases. When this process occurs on cytosine, the base is converted to uracil. Deamination occurs during the lifetime of an organism, and the modifed bases are spread along the entire length of the DNA. In ancient DNA, deamination is more likely to occur near the ends of fragmented DNA molecules. Therefore the location of deaminated residues on DNA can be used to determine if it is old or a modern contaminant.

Tissues from a 439 year old mummy found in a church in Naples, Italy, were subjected to deep sequencing. Sequences of HBV were identified in 5 tissue samples. A nearly complete genome sequence of hepatitis B virus was assembled from the data. The viral genome was identified as a sub genotype D3 virus which is common in the Mediterranean region. Mitochondrial DNAs indicated an Eastern European host, while deamination patterns were consistent with the presence of ancient DNA, not a recent contaminant.

While the HBV DNA and the mummy are clearly ancient, phylogenetic analysis of the viral genome sequence showed a close relationship with modern genotype sequences. The mummy HBV DNA is not a contaminant, so how can this paradox be explained? When many HBV DNA sequences from the past 50 years are analyzed, no temporal structure can be observed. In other words, it is not possible to determine the age of the mummy HBV DNA by comparing different viral genome sequences. The authors hypothesize that HBV entered humans before 1500, and when the mummy was infected, the virus had already diversified into the ten different genotypes and multiple subgenotypes that circulate today. Mutations do arise during replication of HBV DNA, but these must be removed by selection from the virus population over time. This process likely explains why the HBV genome from a 439 year old mummy closely resembles those from HBV that are circulating today.

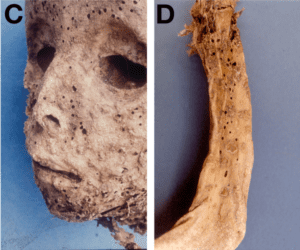

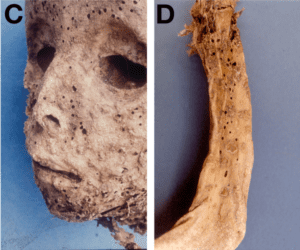

Although a vesiculopustular rash was observed on the arm, body and face of the mummy (pictured), no smallpox DNA was detected. The authors conclude that the child did not have smallpox, but rather Gianotti-Crosti syndrome, a papular acrodermatitis caused by HBV in children 2-6 years of age.

This fascinating story shows that the study of ancient DNA can not only illuminate viral evolution, but also identify the causes of very old infections.

Pingback: A virus and a paradox in a 439 year old mummy - VETMEDICS

Pingback: A virus and a paradox in a 439 year old mummy - Virology