by Gertrud U. Rey

Recent news headlines have been featuring multiple outbreaks of measles across the globe, and an announcement from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention dated January 25, 2024, also reported 23 confirmed cases in the US over the past month. These outbreaks happen every few years and are usually triggered by unvaccinated individuals in regions where childhood vaccination coverage is low. But why is measles virus always the first pathogen to resurface in under-immunized areas?

Measles virus is an extremely transmissible virus that is acquired by inhaling respiratory droplets or aerosols expelled from the cough or sneeze of an infected person. Respiratory droplets that settle on surfaces and aerosol particles suspended in the air may still contain viable viruses when they are picked up and/or inhaled by the next person several hours later. The transmissibility of a pathogen is measured using a “basic reproductive number” (also referred to as the R0), with a higher number indicating higher contagiousness. The R0 for measles virus ranges from 12 to 18, meaning that, on average, one infected person can infect anywhere between 12 and 18 other people who are not immune to the virus. For perspective, one person infected with influenza virus typically only infects one or two other people. This is the main reason why measles is so prevalent in outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases when childhood vaccination rates drop.

To prevent the spread of measles virus, a majority of people in a population needs to be immune and thereby provide a barrier for transmission to the minority of non-immune individuals who are dispersed throughout the population. The threshold for achieving this “herd immunity” is expressed as a percentage, and it varies for different pathogens because it is directly related to a pathogen’s R0. If each infected individual contacts R0 number of people in a population of randomly immunized people, then the population would reach herd immunity if the number of immune people exceeded a percent value equal to (R0-1)/R0. Assuming that the R0 for measles virus is 15 (i.e., the median of 12 and 18) and one inserts this number into the formula above, then (15-1)/15 would equal 93.3%, meaning that 93.3% of the population would have to be immune to measles virus to prevent detectable transmission. The World Health Organization (WHO) has set the herd immunity threshold for measles virus at 95%, a value that is based on a higher R0, and is likely derived from past vaccination and outbreak data. In other words, according to the WHO, about 95% of the population needs to be immunized with the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine at any given time to keep measles at bay.

It turns out that the US has not met this 95% vaccination threshold for several years. One of the reasons for this deficiency is a misguided anti-vaccine bias initiated by the publication of a fraudulent study by a former physician named Andrew Wakefield – a topic discussed in a previous post and video. Even though Wakefield’s paper was eventually retracted and he was banned from practicing medicine, his message had already gained a strong foothold and thousands of children born in the late 1990s and early 2000s are now unvaccinated adults. The COVID-19 pandemic also led to a further decline in global measles vaccination coverage, with 25 million children currently missing their first dose and an additional 14.7 million children missing their second dose of the MMR vaccine.

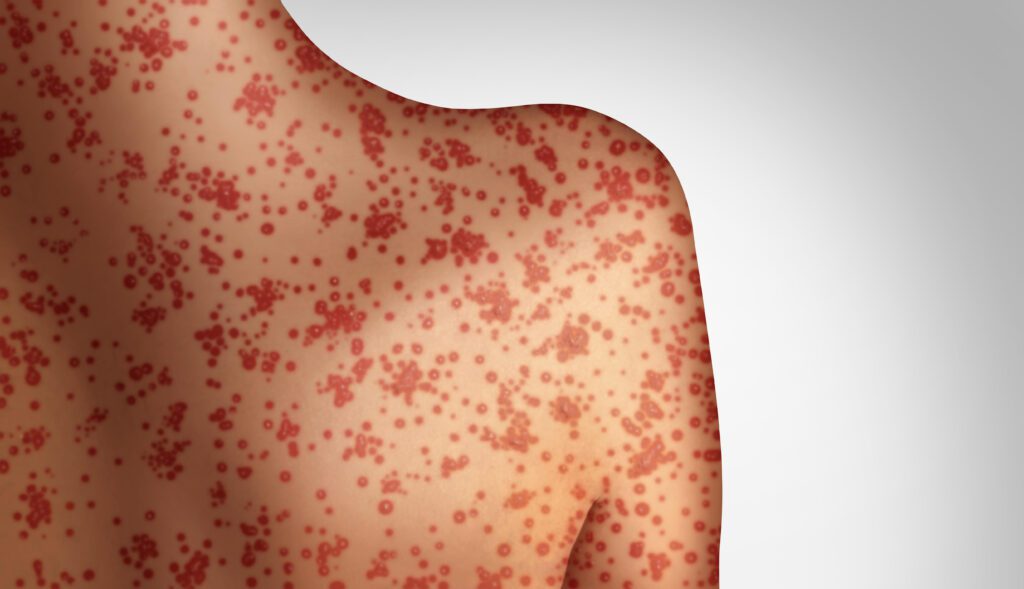

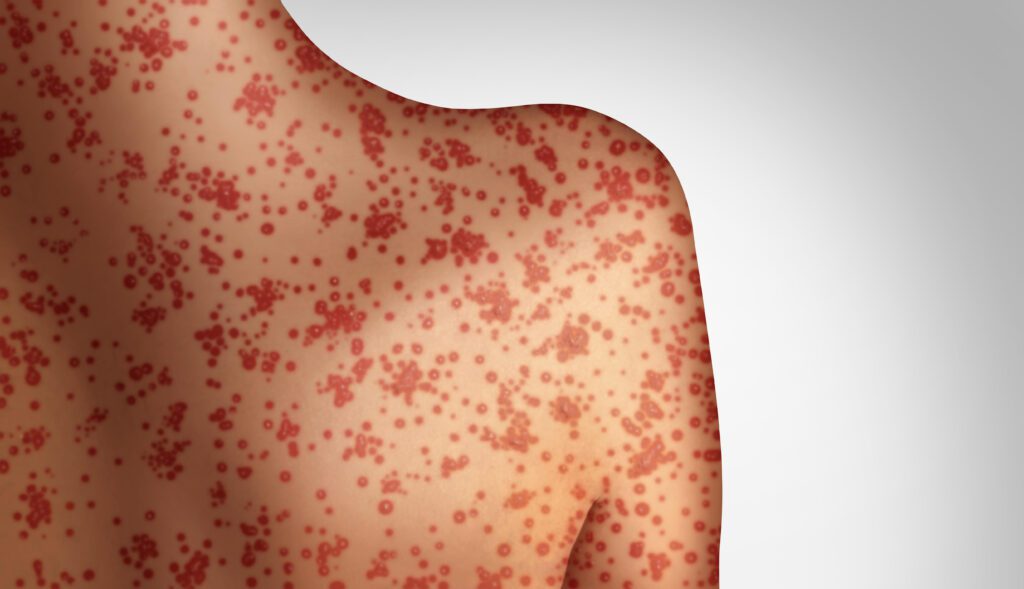

Because measles is non-existent in areas where vaccination rates are high, many are under the impression that the disease no longer exists. However, measles virus will always be around, at the very least because it can be transmitted by asymptomatically infected people.* It is also difficult to appreciate the severity of an illness when one has never witnessed or experienced it. Nevertheless, measles is a serious illness that requires hospitalization for one out of every five unvaccinated and infected people. There are no specific therapeutics available, and treatment consists mostly of supportive care. The infection increases the risk of ear infections, seizures, deafness, and blindness, and about three out of every 1,000 children with measles dies from complications like pneumonia or encephalitis. Furthermore, measles virus infection appears to erase previous immune memory and antibodies to other pathogens, potentially opening the door to countless other infections.

Fortunately, vaccination is a safe and effective way to prevent measles, with two doses of the MMR vaccine providing up to 99% effectiveness against disease. There is simply no reason for anybody to develop measles these days.

[*Although many consider measles virus a good candidate for eradication, there are three essential criteria that need to be met to eradicate a pathogen: 1) it may only replicate in one host (e.g., humans only), 2) vaccination must induce lifelong immunity; and 3) asymptomatic infections should not contribute to the spread of the pathogen. This topic was discussed in a previous post about poliovirus. The material in this blog post is also covered in Catch This Episode 56.]