by Gertrud U. Rey

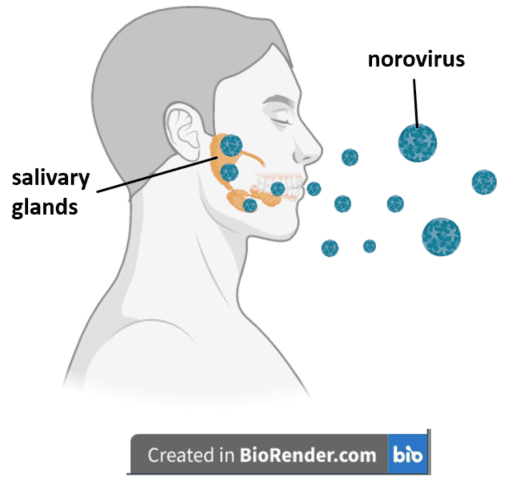

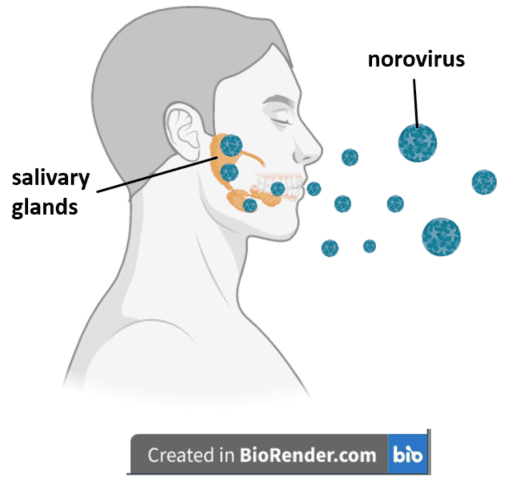

Norovirus and rotavirus are considered to be enteric pathogens because they are traditionally thought to be transmitted by the fecal-oral route; i.e., when consuming food prepared by someone who did not wash their hands properly after using the bathroom. Unlike rabies virus, which replicates in the salivary glands and transmits through saliva, the presence of noroviruses and rotaviruses in saliva is usually considered to result from contamination, for example by vomitus or gastroesophageal reflux.

It was therefore surprising when a recent study showed that neonatal mice (“pups”) can apparently transmit enteric viruses to their mothers during suckling. Following oral inoculation with mouse norovirus 1 (MNV-1) or epizootic diarrhea of infant mice (EDIM, a mouse rotavirus), pups had secretory IgA (sIgA) in their intestines that increased gradually over the course of two weeks. sIgA is a type of antibody that provides immunity in mucous membranes such as those of the mouth, nose, and gut, and sIgA is typically passed from mothers to infants during suckling. Interestingly, this sIgA increase in pups correlated with a similar increase in the sIgA in the milk of the mothers, even though the mothers were not infected and did not have any antibodies to either virus at the start of the experiment (i.e., they were seronegative). Considering that pups can’t produce their own sIgA, it is likely that the pups infected the mothers during lactation, who then produced the sIgA and passed it back to the pups through their milk.

To rule out the possibility that the mothers became infected by consuming feces-contaminated food (i.e., by the traditional fecal-oral route) because they shared a living area with their infected pups, the authors orally inoculated pup-free seronegative mothers with EDIM, treated them with oxytocin to induce milk production, and analyzed the milk for sIgA and the mammary glands for viral RNA. Although the mothers were successfully infected, as evidenced by the presence of EDIM RNA in their small intestines, there was no detectable EDIM RNA in their mammary glands or detectable increase of sIgA in their milk. This result confirmed that the infected pups passed the virus to the mothers during feeding.

To further substantiate this finding, the authors orally infected one set of pups (pups A) with EDIM and placed them back in the cage with their seronegative mothers (mothers A) for suckling. The next day, mothers A were replaced with “mothers B” from a cage of uninfected pups (pups B), and mothers A were placed with pups B. Two days after this switch, all mice were euthanized and analyzed for the presence of viral RNA. All mothers had EDIM RNA in their mammary glands, suggesting that both sets of mothers became infected by suckling pups A. All pups had EDIM RNA in their small intestines, suggesting that pups B became infected by feeding from mothers A, or by ingesting their fecal matter.

The next set of experiments aimed to determine whether saliva contains enteric viruses and if it could serve as a means for transmission. Infection of adult mice with MNV-1 or EDIM revealed that these mice produced and shed virus in their saliva for up to ten days post infection. To see whether this saliva was infectious, the authors fed it to pups as a means of inoculation. At three days after infection, the pups had significantly high viral genome levels in their intestines, comparable to those observed in pups inoculated with virus of fecal origin. This result suggested that the viruses replicated in the intestines and confirmed that saliva can be a conduit for transmission of these enteric viruses.

In an effort to see whether these viruses replicate in the salivary glands, the authors orally infected pups and adults with various strains of norovirus and then isolated their submandibular glands – the largest component of the salivary gland complex. They then measured the number of infectious viral particles inside the submandibular glands using an alternative to the classical plaque assay known as a TCID50 assay, which quantifies the amount of virus needed to infect 50% of cells in culture. Each of the viruses increased in quantity by about 100,000-fold throughout the following three weeks compared to the input level, suggesting that noroviruses do replicate in the salivary glands. Treatment of mice with 2’-C-methylcytidine, an inhibitor of the norovirus polymerase enzyme, led to a decline of virus in the salivary glands, suggesting that this enzyme inhibited viral replication, and confirming that replication occurred inside the salivary glands.

TCID50 analysis of various cell populations isolated from the submandibular gland revealed that MNV-1 replicates in epithelial and immune cells, both of which express Cd300lf, the gene encoding the intestinal receptor for all known strains of mouse norovirus. MNV-1 infection of mice lacking the Cd300lf gene led to no detectable MNV-1 replication in the salivary glands, suggesting that this receptor is needed for infection of submandibular gland cells. Partial extraction of the salivary glands from adult mice before inoculation led to faster clearing of the intestinal infection, suggesting that the salivary glands may serve as reservoirs for replication of these viruses.

The results of this study challenge the notion that noroviruses and rotaviruses transmit primarily by the fecal-oral route and raise several interesting questions. Do human noroviruses replicate in salivary glands, and do humans transmit noroviruses through saliva? If so, would protective measures in addition to handwashing (like face masks) prevent transmission of noroviruses? Are other enteric viruses (like poliovirus) also transmitted through saliva? It will be interesting to see future studies that address these questions.

[This paper was discussed in detail on TWiV 915. The material in this blog post is also covered in Catch This Episode 38.]

Pingback: Transmission of Enteric Viruses through Saliva - Virology Hub

These statements/questions (“rabies virus … replicates in the salivary glands” … “Do human noroviruses replicate in salivary glands” … “noroviruses do replicate in the salivary glands” … “to see whether these viruses replicate in the salivary glands”) concerning replication in “Transmission of Enteric Viruses through Saliva” should be replaced with “are replicated” (or the like), because viruses do not replicate themselves.

Virology blog’s take on it:

“Viruses are not living things. Viruses are complicated assemblies of molecules, including proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, and carbohydrates, but on their own they can do nothing until they enter a living cell. Without cells, viruses would not be able to multiply. Therefore, viruses are not living things … Viruses don’t actually ‘do’ anything.” (Virology 101; Virology Blog, 2004).

6q7ozf

Hey Campbell Soup brain (13 August 2022 at 8:37 pm) … stay real because even some top western quantum physicists have become Eastern Mystics (Small Brains Considered – 6).

zkvidr

Malware warning: above link (16 August 2022 at 6:26 am) is classified as malware by any.run