Human monoclonal antibodies that block infection with SARS-CoV-2 are being used to treat COVID-19 patients, but an alternative, antibodies produced in camelids (alpacas and llamas) might have advantages. Camelid monoclonal antibodies can be more cheaply produced in mass quantities in bacteria, and protein engineering can be quickly used to produce a better therapeutic product.

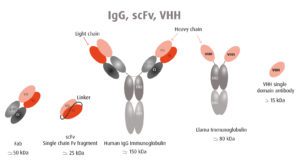

Human antibodies are large proteins made up of two heavy chains and two light chains (pictured). In contrast, camelid antibodies consist only of two heavy chains. Furthermore, the antigen binding domain (VHH in the figure) can be produced on its own in what is called a nanobody. Two VHH domains can be linked together to target separate epitopes (scFv in the figure). VHH single domain antibodies lack the Fc domain, and therefore cannot bind Fc receptors, avoiding antibody-dependent enhancement.

To produce nanobodies against SARS-CoV-2, an alpaca and a llama were immunized with purified spike protein. Three nanobodies from the alpaca and one from the llama were identified that neutralize virus infection of cells in culture. The results of binding and structural studies revealed that three of the nanobodies recognize an epitope on the spike protein that is distinct from the site recognized by the other nanobody.

Three of the four nanobodies appear to block virus infection of cells by causing the spike protein to change to the post-fusion conformation, which is irreversible. The spike post-fusion conformation is usually attained upon binding to the cell receptor, ACE2, but the nanobodies can trigger fusion in the absence of this protein.

Multivalent nanobodies were engineered by joining VHH domains of two different specificities. These scFv proteins displayed 100-fold improved neutralization of SARS-CoV-2. Furthermore, while variant viruses resistant to neutralization by individual nanobodies were readily selected in cell culture, none were observed after virus passage in the presence of multivalent nanobodies. Delaying the emergence of nanobody resistant variants might lead to better therapeutic efficacy in patients.

Another attractive property of nanobodies is that they can be delivered to the respiratory mucosa by inhalation of aerosols. This delivery method could reduce the dose needed and allow treatment outside of medical facilities. In contrast, human monoclonal antibodies must be administered intravenously.

Whether or not nanobodies help end the COVID-19 pandemic is unclear. However their clinical development should continue as they may be useful in the case of outbreaks in immunocompromised individuals who cannot be vaccinated. What is learned from their development against SARS-CoV-2 will likely save lives when the next pandemic inevitably arrives.

Very cool. A test regiment using inexpensive antigen tests (for infectivity) seems like a prerequisite to ensure timely delivery of antibody therapeutics. Spray delivery to the upper respiratory mucosa seems like an ideal way to reduce spread to the lower respiratory and/or gastrointestinal systems where severe pathology seems to occur.

Dear Prof. Racaniello,

Your views on the ‘British variant’ in one of your previous blogs was confirmed by Chantal Reuskens a virologist at RIVM (Dutch CDC) in an article in the Dutch quality paper NRC (wetenschap 16/1-21) and your name was mentioned in the article.

As former student in your virology MOOC – which was one of the best MOOCs I did – I am glad that my understanding of the ‘ways of the virus’ is improved for which I thank you!

hans janus