The patient had received a kidney transplant at the age of 58 in February 1993. Nearly 25 years later he was admitted to hospital with two days of fever, nausea, and vomiting. A sonogram revealed an enlarged right lobe of the liver, but tests for hepatitis A, B, C and HIV-1 were negative. He progressed to hepatic insufficiency and acute liver failure and died 6 days after admission to hospital.

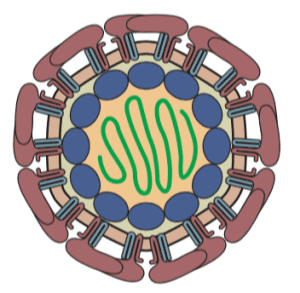

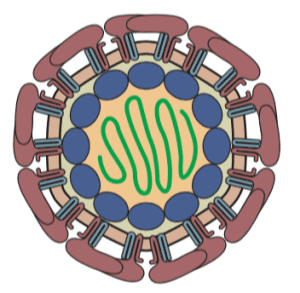

After the patient€™s death, serum that had been collected on the seventh day of clinical symptoms was found to contain the RNA of yellow fever virus, a flavivirus (illustrated). Results of pathological examination of the liver were consistent with a diagnosis of yellow fever.

The patient lived in an urban area of Brazil, 6 kilometers from a city park that harbored monkeys that were positive for yellow fever virus. In light of the potential for yellow fever, transmitted by mosquitoes, inhabitants of the area around the park had been given yellow fever virus vaccine. However, because the transplant recipient was immunosuppressed due to his transplant, he did not receive the vaccine.

The danger to immunosuppressed transplant recipients of yellow fever virus vaccine, an infectious, attenuated vaccine, is unclear. There are no reported cases of yellow fever in vaccinated transplant recipients. Some transplant recipients (n=39) have inadvertently received yellow fever vaccine, but none had adverse effects. Nevertheless there are insufficient data to indicate that yellow fever virus vaccine is safe in transplant recipients.

This case represents the first occurrence of yellow fever in a transplant recipient. As the authors write, ‘this case shows the great dilemma posed to doctors: how to advise an immunosuppressed patient living in an area affected by yellow fever€™? Yellow fever is a serious disease with high mortality rates; yet the vaccine is contraindicated in immunosuppressed patients.

I suspect that the incidence of yellow fever in this patient group will increase, as organ transplants become more common and mosquito range increases due to climate change. One solution might be to have antiviral drugs and neutralizing monoclonal antibodies available to treat transplant recipients who live in areas where yellow fever is endemic. Such treatments do not currently exist, but they could be readily developed and tested. And they could also be used to treat the many cases of yellow fever that occur each year in unvaccinated individuals.

Pingback: Fatal yellow fever in a transplant recipient - Virology Hub

A sad and very unlucky case.

It makes me wonder, though, about the trope we often hear, that pandemics due to reservoirs of unknown viruses being uncovered as rainforests continue to be cleared. In view of the ever increasing pace of deforestation, development, urbanisation, and extermination by Man of most larger animals, birds, (and even more plants): isn’t it more likely that the chances of uncovering new deadly diseases and disease vectors must go into decline, and, probably quite soon, approach zero, at the point where the only apes are in laboratories and zoos, and the bats have been ousted from the plantations that replace the forests?

Yes, when all the nonhuman animals are gone, there will be no more zoonotic viruses. But despite our progress in such extermination, it will still take a long time, and meanwhile, there will be new viruses.