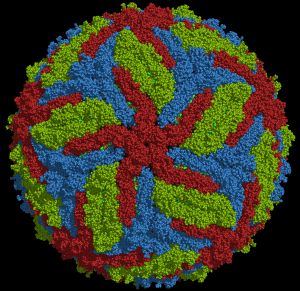

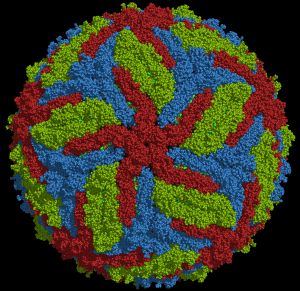

Inoculation of mice with the flaviviruses West Nile virus (WNV) and Zika virus (ZIKV, pictured) led to viral replication throughout the intestinal tract and dilation of intestinal segments. The dilated bowel was accompanied by defects in the time needed for transit through the intestine. Chikungunya virus, an arthritogenic alphavirus that also causes a systemic infection, did not dysregulate GI motility.

Viral replication in mice was observed within enteric neurons, and caused cell death, but did not take place in glial cells or mucosal epithelial cells. Changes in GI motility after virus infection required CD8+ T cells and is therefore immune mediated.

Animals that survived WNV infection showed defects in GI motility as late as 4 to 7 weeks post-infection. Inoculation of these mice with an attenuated strain of WNV or synthetic RNA (polyIC) caused a slowing of GI transit independent of immune cell infiltration. These observations mimic the findings in humans that symptoms of GI dysmotility disorders may be episodic, following infection or inflammation.

It has previously been suggested that a subset of GI motility disorders in humans occurs after infections with viruses, bacteria, or protozoans. The results of flavivirus infection of mice described here are consistent with this hypothesis. The findings also suggest that infection of enteric neurons by neurotropic viruses can not only cause an acute episode of GI dysfunction, but also induce a chronic disorder that can be periodically exacerbated by additional infections or inflammation.

It is unlikely that flaviviruses are a significant cause of GI dysmotility disorders because these infections are not common in humans. It is more likely that other widespread enteric infections, such as those caused by enteroviruses, might be responsible for these diseases.

Enteroviruses are good candidates for causing human GI dysmotility disorders not only because they are common, but many are neurotropic and infect the GI tract. Understanding the role of these viruses in intestinal dysmotility will require large epidemiological studies that attempt to correlate infection prevalence (determined by serological studies) with GI symptoms. Should enteroviruses be implicated in these disorders, an intriguing question will be why only a fraction of those infected develop the disorders. The answer likely lies in the genome, in genes that regulate immune responses to infection.

Pingback: Viral infections of the enteric nervous system and intestinal dysmotility -

Pingback: Viral infections of the enteric nervous system and intestinal dysmotility – Virology