Here is why I’m fascinated by giant viruses: when they were first discovered (Mimivirus, 2003), not only were they the largest ever found, but they had huge genomes that encoded many proteins that had never before been seen. These genomes also encode proteins that participate in protein synthesis – another first for viruses.

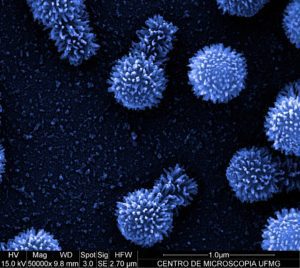

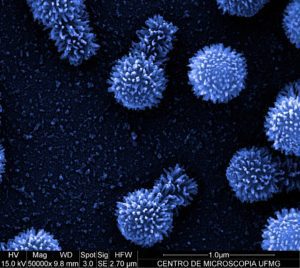

The new giant viruses – there are two of them, isolated from soda lakes in Brazil and deep ocean sediments – are called Tupanvirus. The capsid looks like a Mimivirus, but it is attached to a long, cylindrical tail – which, according to the authors, is ‘the longest tail in the virosphere’ (pictured; image credit). The function of this tail is unclear – during infection, its contents appear to exit into the cytoplasm, but the viral DNA exits directly from the capsid. In other words, the tail does not appear to serve the analogous function in tailed bacteriophages, to bring the viral DNA from the head into the host cell.

With each new giant virus discovered, we expect still more novel genes, and Tupanvirus does not disappoint. The genomes are 1.4 and 1.5 million bases of double-stranded DNA (the fourth largest viral genomes known), encoding 1276 and 1525 predicted open reading frames. Of these, 375 and 378 are ORFans – unlike anything we have seen before. I found amazing the fact that nearly half of the 127 proteins in the virus particles are also unknown!

Perhaps the most striking feature of Tupanvirus is that the genome encodes the largest set of proteins involved in translation. Included are all 20 aminoacyl tRNA synthetases, 70 tRNAs, multiple translation proteins, and more. I love how the authors summarize this stunning array of protein synthesis components: ‘only the ribosome is lacking’ (although ‘only’ seems a bit of an insult to these very large protein synthesis machines).

The presence of all these genes related to protein synthesis begs at least two questions: what is their function, and where did they come from? We can only speculate, but perhaps by producing a large part of the translational machinery, viral mRNAs can be more efficiently translated. This explanation is consistent with the finding that the codon and amino acid usage of Tupanvirus is different from the amoeba that it infects.

As for where these genes came from: there are at least two ideas for the origin of viruses. They might have started out with very small, minimal genomes, and grew larger by the acquisition of genes from other organisms; or they might have started out very big, and lost the genes they did not need. Either scenario could explain the presence of many genes relating to protein synthesis. The authors point out that they cannot discern whether or not the 20 aminoacyl-tRNA synthetase genes came from cells. Yes, more work needs to be done.

Recently someone asked me why they should care about these giant viruses, because they don’t cause human disease. My answer is that they provide insight into the origin of viruses. To know about the viruses that are infecting us today, we need to understand how they got here.

Pingback: Only the ribosome is lacking - Vetmedics

Pingback: Only the ribosome is lacking – Virology