The latest study was conducted in late 2007 and comprised 3415 subjects living in 14 rural villages in the Kasai Oriental Province of the Democratic Republic of Congo. Three outbreaks of Zaire ebolavirus (EBOV) had occurred in this country in 1976, 1977, and 1995, and one was ongoing nearby at the time of sampling.

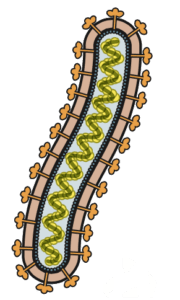

To detect antibodies against EBOV, an ELISA format was used in which plastic plates were coated with purified recombinant viral nucleoprotein. These were incubated with serum specimens followed by addition of a second antibody conjugated to peroxidase. A chromogenic substrate was then added and optical density was determined as an indication of the level of antibodies binding to the immobilized nucleoprotein.

The results show that 11% of all subjects were positive for IgG antibodies against EBOV nucleoprotein. Risk factors for being EBOV seropositive included the following:

- Increasing age: those 15 years and older had a 3 times odds of being seropositive

- Male (1.5 times)

- Resident of Kole (1.6 times, nearest to ongoing outbreak)

- Hunting, butchering, cooking and eating forest animals

- Exposure to rodents and duikers

These observations add to previous serological surveys which demonstrate that antibodies to EBOV are present in many individuals. The results of one study revealed antibodies in 10% of individuals in non epidemic regions of Africa. A similar fraction (9.5%) was reported in villages near Kikwit, DRC where an outbreak occurred in 1995; in the Aka Pygmy population of Central African Republic (13.2%), and in 220 villages in Gabon (15.3%). No Ebola hemorrhagic fever cases were reported in these areas.

These EBOV seropositive individuals likely had either asymptomatic, or minimally symptomatic infections in the absence of an outbreak.

Why the infection is more lethal during outbreak conditions is not known. One possibility is related to the size of the viral inoculum received. During outbreaks the virus is spread by contact with the blood, secretions, organs or other body fluids of infected individuals, which contain very large quantities of virus. In contrast, infections in nature €“ by contact with contaminated fruit, for example €“ may involve far less virus. The route of entry into the host might also make a difference. Outbreak cases often acquire infection by direct contact with the blood and other body fluids of patients with severe disease. The natural route of infection might instead involve oral or respiratory entry of animal body fluids.

It is also conceivable that during EBOV outbreaks, a certain fraction of infected individuals develop minor symptoms and these infections are never detected. This idea is consistent with the finding that antibodies against EBOV were detected in 2.6-6.5% of the sera of asymptomatic close contacts of EBOV cases in the 2013-16 outbreak in West Africa.

The apparent EBOV seropositivity observed in these and previous studies could be the consequence of infection with a related, but non-pathogenic filovirus; or perhaps even the result of EBOV entering the body and stimulating an immune response in the absence of an infection.

Pingback: Ebolavirus infections but no outbreak - Virology

Pingback: Ebolavirus infections but no outbreak - VETMEDICS