Bacteriophages determine the composition of microbial populations by killing some bacteria and sparing others. Bacteriophages are typically host specific, a property that is largely determined at the level of attachment to host cell receptors. How resistant and sensitive bacteria in mixed communities respond to phage infection has not been well studied.

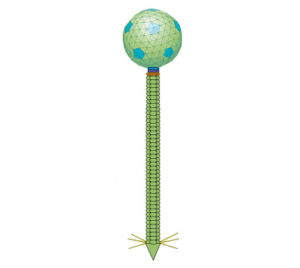

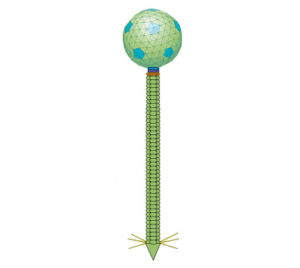

Several phages (including SPP1, pictured) of the soil bacterium Bacillus subtilis first attach to poly-glycosylated teichoic acids (gTA), and then to the membrane protein YueB, leading to injection of DNA into the cell. Cells that lack the gene encoding either of these proteins are resistant to infection.

When a mixed culture of resistant and susceptible B. subtilis cells were infected with phage SPP1, both types of cells became infected and killed. Infection of resistant cells depended on the presence of susceptible cells, because no infection occurred in pure cultures of resistant cells.

Both infected and uninfected bacteria release small membrane vesicles that contain proteins, nucleic acids, and other molecules. Phage SPP1 can attach to membrane vesicles released by susceptible strains of B. subtilis, showing that they contain viral receptor proteins. Furthermore, phage SPP1 can infect resistant cells that have been incubated with membrane vesicles from a susceptible strain – in the absence of intact susceptible cells.

These results show that membrane vesicles released by susceptible bacteria contain viral receptors that can be inserted into the membrane of a resistant cell, allowing infection. Because phage infection can lead to transfer of host DNA from one cell to another, the results have implications for the movement of genes for antibiotic resistance or virulence. It’s possible that such genes may move into bacteria that have only ‘temporarily’ received virus receptors via membrane vesicle transfer.

These findings should also be considered when designing phage therapy for infectious diseases. The idea is to utilize phages that are host specific and can only destroy the disease-producing bacteria. It’s possible that the host range of such phages could be expanded by receptor protein transfer. As a consequence, unwanted genes might make their way into ‘resistant’ bacteria.

I wonder if membrane vesicle mediated transfer of receptors also occurs in eukaryotic cells. They shed membrane vesicles called exosomes, which contain protein and RNA that are delivered to other cells. If exosomes bear receptors for viruses, they might be able to deliver the receptors to cells that would not normally be infected. The types of cells infected by a virus would thereby be expanded, potentially affecting the outcome of viral disease.

Great information! thanks for sharing.

Fascinating story. I would think exosomes released by eukaryotic cells must carry membrane proteins. As I am starting immunologist I wonder – why not go further with this idea. Perhaps there could be transfer of immune receptors between cells. For instance – regulatory T cells have been shown to secrete exosomes (with eg. microRNA) which are involved in immune regulation. Perhaps immune cells could transfer receptors and, provided the recipient have the appropriate machinery, could, eg. promote response to specific pathogen.

Thanks for sharing the story!

Pingback: viruses | [Veterinary and Medical Sciences

Pingback: Giving your neighbor the gift of virus susceptibility – Virology