The reason for the switch is clear: type 2 poliovirus was declared eradicated last year, and the only remaining cases are cause by vaccine-derived type 2 polioviruses. After oral administration of poliovirus vaccine, the virus replicates in the intestine, conferring immunity to subsequent infection. In all recipients of the vaccine the viruses lose the mutations that make them safe for humans. Consequently a small number of recipients, and their contacts, contract poliomyelitis from the vaccine.

To prevent further cases of poliomyelitis caused by circulating vaccine-derived polioviruses, WHO planned a synchronized, global switch from trivalent OPV to bivalent OPV on 17 April 2016. By July of 2016 all remaining stocks of the Sabin type 2 poliovirus strains, which are used to produce OPV, will also be destroyed.

My concern with this strategy is that type 2 vaccine-derived polioviruses continue to circulate. Whether they will continue to do so long enough to cause an outbreak of paralytic disease in the cohort of new infants that do not receive type 2 vaccine is a mattern of conjecture. In case there is an outbreak, monovalent type 2 oral poliovirus vaccine is being stockpiled by WHO. Of course, re-introduction of this vaccine will be accompanied by more circulating vaccine-derived poliovirus in the environment, and vaccine-associated disease, the very event WHO is trying to end with the trivalent to bivalent switch.

Type 3 poliovirus has not been isolated since 2012. Only type 1 poliovirus still causes outbreaks in two countries: Pakistan and Afghanistan. The inability to vaccinate in those countries, due to conflict, is delaying eradication. The recent killing of seven police officers who were protecting polio vaccinators by the Pakistani Taliban is an example of this difficulty.

Developing a great vaccine is not the only requirement for preventing infectious disease: you also have to be able to deploy it.

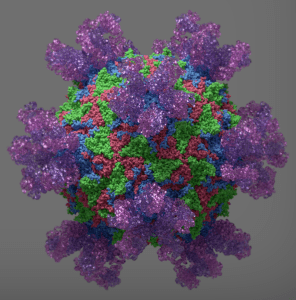

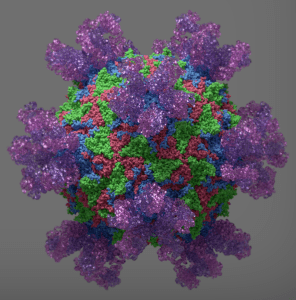

Image: Antibodies bound to poliovirus by Jason Roberts.