Three boxes full of dry ice arrived in the laboratory in August 1986. In them were sixty-six containers of different polioviruses that Dr. Schaffer had collected over the years. All three poliovirus serotypes were represented, both wild type and vaccine strains. The tubes were marked with dates ranging from 1948 to 1965. Most had come into Dr. Schaffer’s hands from well known poliovirologists, including Jonas Salk, Albert Sabin, Igor Tamm, Renato Dulbecco, and Charles Armstrong.

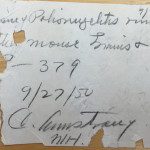

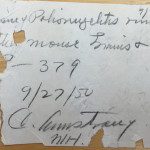

All of the samples were in glass containers, either tubes with a screw cap or a rubber stopper held in place with tape (pictured). A few were in glass bottles of the type that were used to grow cells. The collection held not a single plastic tube: these were the days before plastics entered the virology world. All were identified by hand-written labels on white cloth tape. Some of the labels in the photo read: Polio 1 Brunhilde (1963), Polio 2 MEF1, Polio 2 P712, HeLa P3, 10-21-62. Nearly all the samples were virus-containing cell culture supernatants.

I have since transferred most of the samples to plastic tubes which are stored in a -70C freezer. There is a trove of information to be obtained by studying these samples, but there are few poliovirologists left who are interested. Once poliomyelitis is eradicated – perhaps within the next 10 years – these samples, and similar ones throughout the world, will have to be destroyed.

Great that you have preserved these samples – but a longer-term strategy needs to be adopted, before completely irreplaceable specimens are lost forever, to you and to science in general.

I have the same problem: a colleagues’ samples of plant viruses; beautifully preserved in heat-sealed glass vials, dried over silica gel, dating back in some cases to the early 1960s. For that matter, I have about a thousand glass bottles of liguid plant virus samples at 4degC, dating back in some cases over 40 years – and still viable.

Surely there is a case to be made for preserving some of these viruses? Mining them for sequence in this metagenomic age is not that difficult; preserving their infectivity, however – another matter. Some of my plant viruses are probably bomb-proof; your poliovirus samples, on the other hand – probably slowly deteriorating as we watch.

A wider conversation is needed: I know of other archives, of old poxvirus collections for example, that will be lost forever in a few years. Should we not get an international effort going to log them, sequence them, preserve them?

I think so.

Want to join in?

Yours,

Ed

Pingback: How should we preserve old viruses? | ViroBlogy

The preservation of such collections is a tough problem, because it costs money. ATCC, for example, is not interested, but they are so underfunded that it’s not surprising. At least for poliovirus (and already smallpox) the other issue is that most collections will have to be destroyed. It would certainly be worthwhile to deep sequence them, at the least. Happy to join in.

Archiving specimens and raw data such as laboratory notebooks is a very longstanding and underappreciated problem in science. One might think that government-funded research materials would be stored for posterity in some public place, but they’re generally not. The individual scientists are left holding all of these – sometimes priceless – items, and there’s no standard procedure for handling them.

Having recently retired, I have been through this process. I had three collections of temperature sensitive mutants of vaccinia virus: mine, Sam Dales and Marcia Ensinger, plus some miscellaneous variant and engineered vaccinia mutants of mine. Thinned down some, this came to about 300 samples. As has been noted, no official organization was willing to deal with this size collection. I broadcast to the pox group at a meeting my intention to destroy these collections if I could not find a home, and this garnered two laboratories willing to take the collections for safekeeping and distribution to other scientists who might want samples. I made two annotated copies of the collections. One has been sent to one laboratory, and the other is waiting in Florida for my return from my retirement walkabout when it will be shipped to another laboratory. This is a temporary solution, maybe 10-20 years. If no one taps this resource during that time, then destruction is appropriate.

Speaking of which, I hereby confess with some melancholy that in this closeout process a collection of poxviruses from Joe Sambrook were destroyed. These were mostly rabbitpoxviruses, both temperture sensitive mutants and host range deletion mutants, plus as I recall a couple of strains of vaccinia and maybe a vial or two of adenovirus. Similar to Vincent’s poliovirus collection, these were freeze dried samples in sealed glass ampules with handwritten lettering on the outside. They were acquired from Joe by Dick Moyer when Dick initiated his poxvirus work. For scientists like Dick and myself, they had great historical significance. They were isolated when Joe was working with Frank Fenner. I believe they were part or most of Joe’s Ph.D. work with Frank. I would have to verify this but I think it is possible that the ts mutants were some of the first if not the first ever isolated in an animal virus, and for me they were proof of principle that isolation and characterization of ts mutants in poxviruses was practical, forming a basis for my own work. Perhaps more important, the host range deletion mutants (as it turned out) were the first mutants in virus immune modulatory genes and in that way ultimately launched the whole field of virus mediated immune modulation. Dick and I discussed at length what to do with these viruses. He had used the key mutants in his own work and characterized them extensively. Otherwise these had been sitting in a box wrapped in paper towels (presumably by Joe) for nearly 40 years. In the current cirumstances, they would be awkward to keep and have not been touched for so long so we reluctantly decided together that it was time to pull the trigger. They went into the autoclave with appropriate ceremony. I feel a deep sense of gratitude to Joe and a sense of profound privilege for even being able to understand and appreciate the history and value of these now extinct samples.

Great story, Rich. I’m sure there are many others like it that unfold as people retire. It’s too bad there isn’t a way to archive all these great samples. Usually it is done ad hoc, as your experience and mine illustrate.

PS: I also just found rat, mouse, rabbit blood and something I believe to be my ex-PhD supervisor’s blood in a box in my store…perfect for trawing my soon-to-be-made rabbit scFv Ab library with, AFTER we trawl for papilloma- and bunyaviruses…B-)

Pingback: A collection of polioviruses | Dengue and other...

At the (UK) National Collection of Pathogenic Viruses we do archive viruses, but we have limitations on what we can store. Freezers cost money to run, and there has to be justifiable reason to spend public funding. We are deep sequencing everything in the Collection too. I think metagenomic sequencing of the old collections would be a great way of preserving the information, if not the actual viable (?) material itself. I’d be keen to get involved in an archive sequencing project application. (NB these are my own views, not those of Public Health England)