In the introduction to their paper, published in the Journal of Virology, the authors note other problems with many of the studies of XMRV in CFS patients:

- Too small control populations

- Patient and control samples collected at different times

- Investigators generally not blinded to sample identity

- PCR assays that rely on conservation of viral sequence mainly used

- Limits of detection, reproducibility, and precision of assays unknown

- Controls for each step that would identify analysis not done

- Insufficient numbers of negative controls included

- No study included positive samples from the original 2009 patient cohort of Lombardi et al.

To address these issues, the authors collected blood from 105 CFS patients and 200 healthy volunteers in the Salt Lake City area. One hundred of the patients fulfilled both the CDC-Fukuda and the Canadian consensus criteria for diagnosis of ME/CFS. The patients were selected from a clinic that specializes in the diagnosis and management of CFS and fibromyalgia.

New blood samples were also collected (by a third party) from 14 patients from the original study by Lombardi et al. The samples were blinded for subsequent study. Detection of viral nucleic acids was done using four different PCR assays. Anti-XMRV antibodies in patient sera were detected by ELISA. Finally, virus growth from clinical specimens was attempted in cell culture. The authors used the multiple experimental approaches reported by Lombardi and colleagues.

Let’s go through the results of each assay separately.

PCR for viral nucleic acids. Four different quantitative PCR assays were developed that detect different regions of the viral genome. The assay for pol sequences has been used by several groups and is the most specific PCR assay for XMRV. Three other PCR assays were also used that target the LTR, gag and env regions of XMRV DNA. These assays could detect at least 5 viral copies of XMRV DNA. The precision and reproducibility of the PCR assays, as well as their specificity for XMRV, were also demonstrated. DNA prepared from white blood cells of 100 CFS patients and 200 controls were negative for XMRV. For every 96 PCR reactions, 12 water controls were included; these were always negative for XMRV DNA.

XMRV antibodies in human sera. To detect XMRV antibodies in human serum, a portion of the viral envelope protein, called SU, was expressed in cells and purified from the cell culture medium. The SU protein was attached to plastic supports, and human serum was added. Any anti-XMRV antibodies in human sera will attach to the SU protein and can subsequently be detected by a colorimetric assay (we have discussed this type of assay previously). This assay revealed no differences in the amount of bound human antibodies for sera from CFS patients or healthy controls. Some of the patient sera were also used in western blot analysis. Recombinant XMRV SU protein was fractionated by gel electrophoresis. The protein on the gel is then transferred to a membrane which is mixed with human serum. If there are anti-XMRV antibodies in the human serum, they will react with the SU protein on the membrane, and can be detected by a colorimetric assay. When rabbit anti-XMRV serum was used in this assay, the SU protein was readily detected. None of the human sera analyzed by this method were found to contain antibodies that detect SU protein.

Infectious XMRV in human plasma. It has been suggested that the most sensitive method for detecting XMRV in patients is to inoculate cultured cells with clinical material and look for evidence of XMRV replication. The XMRV-susceptible cell line LNCaP was therefore infected with 0.1 ml of plasma from 31 patients and 34 healthy volunteers; negative and positive controls were also included. Viral replication was measured by western blot analysis and quantitative PCR. No viral protein or DNA was detected in any culture after incubation for up to 6 weeks.

Analysis of previously XMRV-positive samples. Blood was drawn from twenty-five patients who had tested positive for XMRV as reported by Lombardi et al. These samples were all found to be negative for XMRV DNA and antibodies by the PCR and ELISA assays described above. In addition, no infectious XMRV could be cultured from these 25 samples.

Presence of mouse DNA. After not finding XMRV using qPCR, serological, and viral culture assays, the authors used the nested PCR assay described by Lo et al. Although positives were observed, they were not consistent between different assays. This led the authors to look for contamination in their PCR reagents. After examination of each component, they found that two different versions of Taq polymerase, the enzyme used in PCR assays, contained trace amounts of mouse DNA.

Given the care with which these numerous assays were developed and conducted, it is possible to conclude with great certainty that the patient samples examined in this study do not contain XMRV DNA or antibodies to the virus. It’s not clear why the 14 patients resampled from the original Lombardi et al. study were negative for XMRV in this new study. The authors suggest one possibility: presence of “trace amounts of mouse DNA in the Taq polymerase enzymes used in these previous studies”. I believe that it is important to determine the source of XMRV in samples that have been previously tested positive for viral nucleic acid or antibodies. Without this information, questions about the involvement of XMRV in CFS will continue to linger in the minds of many non-scientists.

At the end of the manuscript the authors state their conclusion from this study:

Given the lack of evidence for XMRV or XMRV-like viruses in our cohort of CFS patients, as well as the lack of these viruses in a set of patients previously tested positive, we feel that that XMRV is not associated with CFS. We are forced to conclude that prescribing antiretroviral agents to CFS patients is insufficiently justified and potentially dangerous.

They also note that there is “still a wealth of prior data to encourage further research into the involvement of other infectious agents in CFS, and these efforts must continue.”

Clifford H. Shin, Lucinda Bateman, Robert Schlaberg, Ashley M. Bunker, Christopher J. Leonard, Ronald W. Hughen, Alan R. Light, Kathleen C. Light, & Ila R. Singh1* (2011). Absence of XMRV and other MLV-related viruses in patients with Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Journal of Virology : 10.1128/JVI.00693-11

Wow, thats pretty amazing. This is amazingly comprehensive work to disprove your own research. Very impressive on their part to do the work the right way and with so many levels of control.

accidental double-comment… remove this one if possible, thanks

As a “non-scientist,” I’d be willing to lay the XMRV connection to rest if scientists as respectable as these have proven it’s invalid. But wait: this otherwise excellent explanation doesn’t explain how traces of mouse DNA could have entered my child’s blood sample, or those of so many other patients not included in studies who have tested positive for XMRV.

The hypothesis is that the reagents used to test whether a child was XMRV positive or not, were contaminated with mouse DNA. The reagents, enzymes and proteins that we use in the lab are generally produced from either bacteria or mammalian cells (often times mouse cells). if the preparation of that protein was not done properly it could have brought with it contaminating mouse DNA.

In this case, the XMRV virus is highly infectious to most cells in the laboratory and could have unknowingly infected cells that were used for the experiment. The bigger concern is how the initial samples turned up positive while the resampling of the same people is now negative. There is a much more rigorous process of controlling and cleanliness of the procedures in this paper that may have been lacking in the previous paper and could have contributed to the contamination of the initial samples.

The important thing is that this seems to be settled and that CFS patients know to not request antivirals for treatment as they will not help them at all.

I’m still confused as to how I can show XMRV positive by blood, serum, culture, and have antibodies?. How can this be explained as contamination? Please help me out here.

“It’s not clear why the 25 patients resampled from the original Lombardi et al. study were negative for XMRV in this new study. The authors suggest one possibility: presence of “trace amounts of mouse DNA in the Taq polymerase enzymes used in these previous studiesâ€.”

The obvious alternative explanation is that this part of the study directly indicates that their assays are incapable of detecting genuine clinical isolates. If their assays, like many of the previous negative studies, are highly specific to the VP62 clone, this is a very real possibility.

Unless I’m missing something, the paper says 14 people from the original study were sampled, not 25. The researchers state they did not know what the WPI results were for these 14 people until after their study was completed. Judy Mikovits is thanked for helping coordinate the sample collection and Frank Ruscetti advised them on the spin inoculation protocol.

Pingback: Sinking Feeling: Another Study Doesn’t Find XMRV and Other MLV-Related Viruses in ME/CFS Patients | Thoughts About ME

That simply isn’t true I’ve been on antivirals for months now and I am functioning for the first time in 5 years.

Would suggest emailing the corresponding author and asking for a PDF reprint so you can read the paper, it’s very detailed on the methodologies used.

OK fair enough about the reagents. But lets say that is an explanation for the positive results – one inconsistency that I don’t see explained is how reagents that have mouse DNA in them can select for “sick” patients consistently in two studies. If the batches of reagents were contaminated, you’d think that the distribution of “positive” results would have been more normal among patients and controls in the Lombardi and Lo papers. But instead, both papers found “positives” almost exclusively in samples that when unblinded were originally from patients with symptoms. This even when the Lombardi study used labs at 3 different geographic locales and samples went directly to each lab as opposed to passing through a common source. There is something that still doesn’t make sense there.

Also, both Lombardi and Lo claim to have tested their labs, materials, cell lines, etc.. for mouse DNA contamination multiple ways and come up negative. They could have missed something I suppose, and I guess they should compare their methods to Singh. But just because one lab has reagents, lines, etc.. that are compromised doesn’t mean other labs do. It just means that it is possible.

Furthermore, a few weeks ago the “contamination” argument reseted on the idea that XMRV was actually there, coming not from the patient samples, but from the cell line itself when combined with the samples. Assuming the assays used in this paper can correctly detect the diversity of XMRV strains that might show up in patients, this paper seems to argue against the premise of “cell line contamination” as proposed by Coffin et al. Singh combined their samples with LnCAP and nothing showed up. That, combined with the statements that Lombardi has tested LnCAP multiple times for mouse DNA and XMRV before using it, would argue that LnCAP isn’t the source of contamination as 22rv1 seemed to be in those other papers. Also, like my statement on the inconsistency with the reagents, if the cell line were the source of contamination and all samples (patients and controls) were cultured the same, you’d also expect that the distribution of positives to be more similar between groups.

Do we know that the PCR and culture methods that this paper used were the exact same as the ones used in Lombardi? I am not discounting any assays developed in Singh’s lab that “should” work. But at this point I’d expect anyone running such a study would have used *exactly* the same methods as Lombardi with no chance for any derrivation before coming to such a conclusion. Even if they went on to use other, newer ones as well.

The figure showing the study design says n=25 for the WPI samples, but the Results section says n=14. My guess is that they intended to collect 25 but only ended up getting 14 – the logistics of a study like this are mind-boggling, so no surprise there. In any case, all of the WPI-positive samples were negative in this study.

Please Google the phrase “post hoc fallacy.”

If I can get away with sharing it under fair use, this is the relevant quote from the paper:

“To test if we could detect XMRV in samples that had previously tested positive or negative for XMRV, we obtained a subset of samples from the original cohort that was used to make the association of XMRV with CFS (12). Using a third party phlebotomy service that collected blood samples in home visits, we obtained blinded whole blood and serum samples from 14 individuals. These individuals had repeatedly tested positive in the last two years when tested by the labs at the WPI, though this information was not available to us till the completion of our study. The Clinical Research department at ARUP Laboratories received these specimens and processed the blood using the same protocols as for our healthy volunteers and CFS patient samples. Thus the samples were never opened in a research lab where XMRV might be present – until they reached us. We tested these samples using all of the assays we developed – four qPCR assays, ELISA and Western blots. None of the samples contained any evidence of XMRV. Serologically, there was no difference in the reactivity to XMRV-SU between healthy volunteers and the WPI cohort (p-value = 0.467, Kruskal-Wallis test), indicating that there was no detectable antibody response that was specific to XMRV in the WPI cohort. Furthermore, we also analyzed the WPI samples using tests utilized in the two studies that found XMRV or XMRV-like viruses in CFS, viz. a PCR assay for gag sequences, both in single-round (12) and nested formats (11), and a test for viral growth in cultured cells (12). Neither of these tests revealed any evidence of XMRV.”

Citation 11 is the Lo PNAS paper and 12 the Lombardi Science paper. The methods section of the paper also explicitly notes that they received “extensive help from Dr. Frank Ruscetti” on the viral growth assay.

Pingback: ‘Ila Singh finds no XMRV in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome’, Vincent Racaniello’s ‘Virology Blog’, 4 May 2011 | ME Association

All new assays, non that have been proven to work. At least on this occasion Singh has clearly stated that her new assays are unable to detect HGRVs in known positives. Why is it standard to use positive clinical samples to calibrate a HIV assay, but not a HGRV assay? Do people with ME not deserve a serious scientific investigation?

With unvalidated assays.

While this seems to be a very thorough paper, I think the conclusion the authors came to with respect to antiretrovirals is potentially premature. This paper didn’t directly test the hypothesis of whether CFS patients would benefit from ARVs–for any reason.

The only surefire way to know whether antiretrovirals would be helpful to CFS patients is for there to be a controlled trial of such drugs with CFS patients that measured response to treatment. There are well known lab abnormalities and objective physical and cognitive abnormalities that could be measured to gauge response to drug. If these things improved on treatment, it would certainly re-enforce the idea that the retrovirus hypothesis likely the correct hypothesis and thus warrants more research.

The idea that ARV drugs are held on some pedestal and shouldn’t ever be used in a trial in any patient who hasn’t tested positive for HIV is a little ridiculous. The side effects of these drugs, while present, are well known for the most part and can be controlled for. Millions of people take them every day and there is probably more safety data on this class of drugs than for almost any other.

CFS patients as a group are incredibly sick and disabled as it is. So the calculation of potential benefit vs. side effect would seem to be in the favor a trial – if it was done properly in a controlled manner so that useful information can be gained from it. Not to mention the fact that other drugs, some with similar or worse side effect profiles (Valcyte, Valtrex, Cidofovir, IV antibiotics, IVIG, Ampligen, etc…) have been studied in CFS before – all before an etiology was pinned down for their justification. Even though trials of those agents didn’t end up unlocking the mystery of CFS and being “the cure”, the information gained by such trials makes up much of what is known about CFS today (albeit not much).

Would it be more elegant to pin down the exact etiology prior to doing any drug trials? Of course. But there is still potential for useful information to be gained by doing such a trial anyways at this point. Think of it like working backwards. At the very least, the results may be able to better focus future research.

This is of course assuming the underlying agent responsible for CFS would be sensitive to the currently licesned ARVs that would presumably used in such a trial. Non-movement of trial parameters in response to ARVs could be potentially misleading as well, seeing that the hypothesized agent, despite being a retrovirus, might not actually be responsive to them. Something to consider when weighing the pros/cons of doing a drug trial with the current state of knowledge.

How does it affect her own work. None of the assays have been validated.

They obtained 25 samples from WPI but only 14 had been previously

tested for XMRV. I’ve amended the post to reflect this.

However, this hypothesis for contamination does not explain all the observations, and is thus incorrect. Again, we are back to maybe’s, with no evidence.

If Singh had reproduced the methodology of Lombardi et al or the validation study Lo et al, it would be a very different scene. As is, it sits somewhere between Erlwein et al and the CDCs study Switzer et al. At least the CDC used the same type of PCR and primers, if not annealing temperatures and cycling times.

The most important thing is that again we have a study that tells us nothing for the same reason the other studies did. Unvalidated assays once again.

This paper shows that some of the WPI samples that tested positive by

PCR are negative in the hands of the Singh group. They suggest as an

explanation PCR kit contamination with mouse DNA. Whether or not that

explains previous PCR positives must be examined. Why the WPI samples

were virus negative is also not known; this is an issue that I also

believe needs to be sorted out. Being positive for antibodies is not

terribly meaningful unless the assay detects only anti-XMRV

antibodies. The assay for XMRV antibodies in Dr. Singh’s paper uses

recombinant XMRV protein, but antibodies to related xenotropic

retroviruses will cross react with that protein. In other words, the

antibodies in your serum need not be against XMRV, but a related

retrovirus.

Correction: I meant to say they obtained 25 names of CFS patients from

WPI, not 25 samples. The 25 individuals were then bled, but only 14

had been previously positive.

The CDC retested 20 samples from the WPI with an invalidated assay, they were all negative. Van Kuppelveld et al retested samples too, all negative. Yet we are meant to believe without evidence that those samples were contaminated. Why did their assays not pick up the contamination them?

This paper is no different than any other negative paper using unvalidated assays. It really tells us nothing. Mouse DNA has been tested for in the two positive papers, both were negative. Tested for by independent labs too. Singh having contaminated kits is not evidence for contamination. Otherwise you are suggesting that a mouse virus would never be accepted as jumping into humans because this would be the excuse every time. Very risky belief when there is a HGRV around.

If Singh was curious of whether her assays worked she should have replicated a proven methodology. So it is not unknown why the samples where negative with her assays, as she did not use a prove method.

Again, we are all left waiting for the next paper that might attempt to take the scientific investigation to the next step.

I can assure you that Dr Singh was praying that she could get positive results from her assays. With all the other evidence that XMRV is not a real human virus that has been published recently, I am sure she wanted the samples to be positive. the fact that she didnt get positives from these samples seriously hurts her credibility and future funding. There is no doubt my mind that she wanted her assays to show positive results.

Why she saw them before and now does not see positives is unknown. It could easily have been sloppy science from a past worker in her lab or bad reagents. Either way, the fact that Singh is disproving that which she so critically fought for makes me trust the data even more.

Yet, they did not use the assays previously shown to work. They also never looked for polytropic sequences.

Next paper please.

The PCR assays used were extremely sensitive (they could detect 5

copies of XMRV DNA) and highly reproducible; furthermore they were

directed against four different regions of the viral genome. There is

no doubt whatsoever that Dr. Singh and colleagues are able to detect

XMRV DNA in clinical specimens.

Neither CDC nor van Kuppeveld tested any WPI samples.

So when they write “Furthermore, we also analyzed the WPI samples using tests utilized in the two studies that found XMRV or XMRV-like viruses in CFS, viz. a PCR assay for gag sequences, both in single-round (12) and nested formats (11), and a test for viral growth in cultured cells (12)” what do you think they are referring to?

The reliability of the antibody tests also seemed to be called into question by the Blood Working Group, which reported different results on samples from the same person taken two days apart.

What is your idea of a validated assay? The only settings in which infection is proven is in the animal models.

Out of the 14 samples previously tested in Lombardi et al, only 2 were positive.

So Singh only retested 2 patients with invalidated assays.

I work with HIV all the time, and I never used positive clinical samples to calibrate any assays.

If you read the whole paper none of the assays are the same as Lombardi or Lo et al.

The paper says: “These individuals had repeatedly tested positive in the last two years when tested by the labs at the WPI, though this information was not available to us till the completion of our study.”

and

“We thank Judy Mikovits for help with coordinating sample collection from the previously tested WPI cohort of patients.”

“For virus detection, we utilized four different TaqMan qPCR assays, PCR assays that had resulted in detection of XMRV or MLV-like sequences in previous studies (11, 12)”

Citation 11 is Lo, 12 Lombardi. The methods section mentions a modification to the nested PCR:

“For the nested PCR, we made 2 modifications to the original protocol (11). We used 1.0 U of Platinum Taq instead of 0.5 U, and added dUTP to the mastermix to prevent subsequent PCR contamination with amplicons.”

Incorrect. All 14 re-bleeds were from WPI patients who were previously

positive for XMRV. Please stop posting false information.

The Lombardi et al results were not based on Nested PCR, and the conditions of what they did use were altered in comparison.

This study by Singh et al. used recombinant XMRV SU protein, while the Lombardi et al. study used the spleen focus-forming virus (SFFV) envelope protein to detect antibodies. If XMRV is not involved in CFS, would it be possible to use the antibody (Ab) response to SFFV envelope protein as a starting point in the search for other viruses that may be present in CFS patients?

Are there methods available to isolate enough of this Ab from patients and screen all known viruses for reaction to this Ab? Supposing presence of this Ab would be confirmed to correlate with CFS.

When one road turns out to be a dead end, a scientist should accept, examine what he has and search for another way out.

How?

I googled it Alan, and your name kept coming up repeatedly.

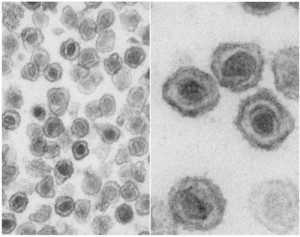

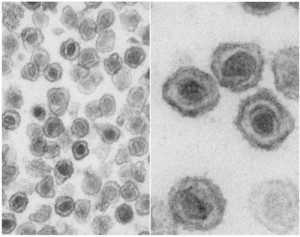

Dr Singhs assays could not detect XMRV in clinical positives from the WPI. She only tested two postive samples from the Lombardi cohort. One of those patients was the source of a sequenced infectious clone and the famous EM image of the budding virus.

She should have said that only two of her patient samples had been shown to be XMRV positives. She used entirely different cycling conditions to Lombardi, Urisman and Lo/Alter.

Even worse she did not use the cycling conditions used by her coleague Schalberg who had detected XMRV in prostate cancer samples. She did not even use the XMRV specific antisera created by Schalberg which was able to detect XMRV in prostate cancer tissue. Schalberg used different forward and reverse primers to account for sequence variability. Singh did not. She claimed that she could not find polytropic sequences when she did not even look for them. This study in fact proves that being able to detect low copy number of VP-62 in a spiked sample does not mean that the assay can detect a polytropic or polytropic/xenotropic MLV in an infected person.

What do you mean how? The information is in Lombardi et al.

I’m sorry but I am not incorrect. Please see the new post I made.

Please see my new comment.

http://healthcare.utah.edu/publicaffairs/news/current/05411Singh.html

This release from the University of Utah contains this passage:

“In her own study, Singh initially obtained false positives for XMRV in blood samples. But she determined those false readings were related to robotic equipment that previously had been used for extraction of DNA from XMRV-infected tissue culture cells. Several months later, this equipment led to new samples getting contaminated. When the robotic equipment was abandoned, no more false positives were detected in either CFS patients or healthy patients. “It’s easy to see how sample extraction and tissue culture processes might be vulnerable to contamination,†Singh said.”

I believe Ila Singh believes very strongly that ME/CFS deserves serious scientific investigation.

One positive outcome of the confusion about XMRV has been that it’s brought so much new attention to the disease; a new generation of scientists has seen for themselves how serious and life-destroying it is, and there are plenty of new promising lines of research to be followed up still, as we saw at the NIH State of the Knowledge conference last month.

ME/CFS being taken seriously as a disease does not – SHOULD not – stand or fall on whether one particular theory of causation turns out to be the right one. Harvey Alter said that this disease has the characteristics of a viral infection, and if XMRV/MLVs turn out not to be the cause, then we need to find out what the cause is.

http://healthcare.utah.edu/publicaffairs/news/current/05411Singh.html

Although she found no evidence for XMRV or any related virus in either her study samples or those tested at the Whittemore Peterson Institute, Singh says there is much data to encourage further research into whether other infectious agents are associated with CFS.

“These research efforts must continue,†she says. “Chronic fatigue syndrome is a devastating disease for which a cure needs to be found.â€

I think the point is well taken that the extreme dismay expressed by some at the idea of CFS patients taking such “serious” drugs as ARVS has been a bit disingenous.

I can only say “right on” to all your points about this – that antiretrovirals aren’t nearly as nasty as they used to be; that they’ve been very extensively studied; that CFS patients are are in fact terribly sick and a ‘serious’ drug isn’t a disproportionate response to that; etc.

On the other hand, the fact that patients have been taking ARVs on a one-off basis is very counterproductive, in my view, and only muddies the waters further with anecdotal reports (in a disease that is relapsing and remitting to begin with) from an completely uncontrolled environments. I’ve always said I’d sign up in a heartbeat for any properly controlled legitimate trial of any plausible treatment; and ARVs have never seemed like the scariest option out there. But I’m not keen on self-experimenting in a way that couldn’t possibly benefit anyone else, since it wouldn’t produce any useful data, and which has an uncertain chance of benefiting me.

By the way, I don’t know if you’re aware that Dr. Montoya’s group at Stanford is continuing long-term trials with antivirals; there’s a link to a recent talk he gave at

http://chronicfatigue.stanford.edu/

So antiviral treatment is certainly not something that’s in the past and abandoned.

Yes, they did.

CDC

“DR. MIKOVITS: I’m Judy Mikovits. I can address that. We have multiple serial samples from patients taken over 20 years, and we have isolated virus from 1984 and the same patient in 2008. In all of the samples that were given to the CDC, we isolated and sequenced whole virus from every one of those 20, suggesting that that assay isn’t clinically validated.”

http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AdvisoryCommittees/CommitteesMeetingMaterials/BloodVaccinesandOtherBiologics/BloodProductsAdvisoryCommittee/UCM225388.pdfSlides

“One of the CDC slides from last week’s Blood Safety Advisory Committee meeting showed that the CDC tested 20 samples from Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (CFS) patients that the Whittemore Peterson Institute (WPI) found to be positive for the retrovirus XMRV. But, according to the slide, the CDC didn’t find any positives among those 20. WPI sent those samples last fall to the CDC, and the CDC tested the samples before submitting its paper to Retrovirology. Did Retrovirology know that the CDC had tested those WPI samples? ”

http://www.cfscentral.com/2010/08/journal-retrovirology-responds.html

Van Kuppelveld

“the samples that you found positive were repeatedly negative upon retesting in our lab.”

http://www.umcn.nl/Research/Departments/kcv/Documents/F%20v%20Kuppeveld%20brief%20naar%20Whittemore.pdf