The story of virophages begins with the giant mimivirus, originally isolated from a cooling tower in the United Kingdom. It is the largest known virus, with a capsid 750 nanometers in diameter and a double-stranded DNA genome 1.2 million base pairs in length. If these statistics are not sufficiently impressive, consider that shortly after its discovery, an even larger related virus was discovered and called mamavirus. These huge viruses replicate in amoeba such as Acanthamoeba; in this host they form large, cytoplasmic ‘factories’ where the DNA replicates and new virions are assembled. While examining mamavirus infected Acanthamoeba polyphaga, investigators noted small icosahedral virions, 50 nm in diameter, within factories and in the cell cytoplasm. They called this smaller virus Sputnik. This new virus does not replicate in amoebae unless the cell is also infected with mimivirus or mamavirus. Surprisingly, infection with Sputnik reduces the yields of mamavirus, and also decreases the extent of amoebal killing by the larger virus.

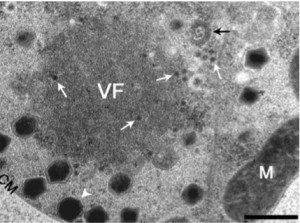

The second virophage is called Mavirus (for Maverick virus – because the viral DNA is similar to the eponymous DNA transposon). Mavirus was identified in the marine phagotropic flagellate Cafeteria roenbergensis infected with – you guessed it – a giant virus, CroV. Like Sputnik, Mavirus cannot replicate in C. roenbergensis without CroV, and it also reduces the yield of CroV particles produced. The figure shows a viral factory (VF) in C. roenbergensis surrounded by large CroV particles (white arrowhead) and the smaller Mavirus particles (white arrows).

There are other examples of viruses that depend on a second, different virus for replication. For example, satellites are small, single-stranded RNA molecules 500-2000 nucleotides in length that replicate only in the presence of a helper virus. The satellite genome typically encodes structural proteins that encapsidate the genome; replication functions are provided by the helper. Most satellites are associated with plant viruses, and cause distinct disease symptoms compared with those caused by helper virus alone. Some bacteriophages and animal viruses have satellites. E. coli bacteriophage T4 is a satellite that requires bacteriophage T2 as a helper, while the adeno-associated viruses within the Parvoviridae are satellites requiring adenovirus or herpesvirus helpers. The hepatitis delta virus genome is a 1.7 kb RNA molecule that requires co-infection with hepatitis B virus to provide capsid proteins.

The difference between Sputnik, Mavirus, and satellites is that the latter do not interfere with the replication of helper viruses. Indeed, Sputnik was termed a virophage by its discoverers because its presence impairs the reproduction of another virus. The name is derived from bacteriophage – the name means ‘bacteria eater’ (from the Greek phagein, to eat). The idea is that one virus impairs the replication of the other – ‘eating’ the other virus.

In addition to their unique effect on their helper viruses, it appears that virophages have other stories to tell. The Sputnik DNA genome contains genes related to those in viruses that infect eukaryotes, prokaryotes, and archaea. Virophages may therefore function to transfer genes among viruses. The relationship of Mavirus to DNA transposons is also intriguing. DNA transposons are a kind of ‘jumping gene’, a piece of DNA that can move within and between organisms. They are important because they can change the genetic makeup of living entities, thereby influencing evolution. It is possible that DNA transposons evolved from ancient relatives of Mavirus, which would give virophages a particularly important role in the evolution of eukaryotes.

Fischer MG, & Suttle CA (2011). A Virophage at the Origin of Large DNA Transposons. Science (New York, N.Y.) PMID: 21385722

Not sure where to post this…

latest news on XMRV… http://www.prohealth.com/library/showarticle.cfm?libid=16037

Pingback: Weekly Round-up 4 « Contagions

Pingback: Virophages engineer the ecosystem

Pingback: Virus That Noms Other Viruses? | Errant Subjects

Pingback: Virophage- the virus eaters « Prabesh's Blog

Pingback: Brent Johnson on virophage

nice theme. but it takes a while to load

Can someone direct my to the article or link that shows that T4 requites T2 for replication. T4 is so widely discussed in lectures and never once have I heard that it’s a satellite!!! Thanks.

Is it possible to make a virophage by genetic engineering to cure Ebola or hiv? You should see what’s the connection between a known virophage to its helper virus then figure out a way to do that for Ebola for example.

Even if you knew how virophages interfere with the replication of their helper virus, this mechanism would not necessarily apply to Ebola virus or HIV. But certainly it’s worth studying how virophages interfere!

While all aspects of the unusual should be studied AND understood, so little is ever written on virophages. They go only so far as to say it can manipulate the genetic codes of all 3 cells involved-the host [amoeba], the the non-eater eating virus [virophage] and the infectious virus [mimivirus]. Viruses do not eat, it gets all it needs from its hosts. So why do articles about the virophagic virus demand that it eats and does not infect? What is being hidden or mis-spoken, or lied about? Several virologists at public and private institutions researching viruses with whom I’ve kindly written to ask these same questions, 4 of 16 responded telling me I’m too stupid to understand, 4 of 16 sent back a blank blank page in my self-addressed and stamped enclosed envelope, 5 had encouragement on my questions but gave no clue or references to help answer my questions, and 3 gave no response. What’s up {or down} with this abundant insolence?

Trust me, it absolutely does not

Pingback: Do giant viruses have a CRISPR-like immune system or a protein restriction factor?

Pingback: Altruistic viruses

Pingback: immunology | [Veterinary and Medical Sciences

Pingback: Altruistic viruses – Virology