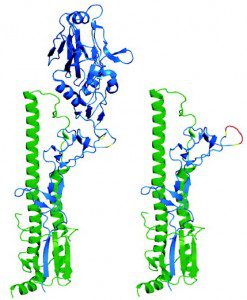

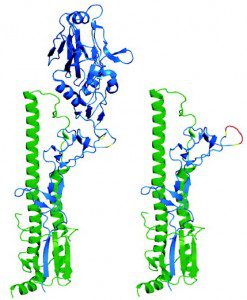

The influenza viral HA protein consists of a globular head atop a stem that is embedded in the virion membrane (figure). Most protective antibodies are directed against the head of the HA molecule. Rare antibodies that block infection with a broad range of influenza virus strains are directed toward the conserved stalk of the viral surface glycoprotein HA. This observation was taken a step further by showing that sequential immunization with different viral HAs, or with HA lacking the globular head, induce broadly neutralizing antibodies. Peter Palese discussed these approaches on TWiV #102.

In another approach, neutralizing antibodies have been induced by immunizing first with plasmid DNA, followed by a boost with recombinant adenovirus encoding the HA protein. Mice were immunized first with plasmid DNA encoding an H1 HA from the 2006-2007 influenza season, then boosted with a recombinant adenovirus encoding the same HA protein. Sera from immunized mice neutralized strains of H1N1 influenza virus dating to 1934, as well as H2N2 and H5N1 viruses. When inoculated with a 1934 H1N1 virus, immunized mice were protected from lethal disease. Immunization of ferrets with a similar regimen also protected these animals from lethal disease. Broadly neutralizing antibodies were elicited in nonhuman primates by this prime-boost regimen.

Both the plasmid DNA and the recombinant adenovirus encoded the full-length HA protein, with both the globular head and fibrous stem. However, the broadly neutralizing and protective antibodies were directed against the stem. Anti-HA stem antibodies were also identified in monkeys that had been immunized with the prime-boost combination.

Why doesn€™t the seasonal influenza vaccine elicit broadly neutralizing antibodies? These vaccines induce antibodies that almost exclusively bind the variable head of the HA, not the conserved stem. The reason probably lies in how the vaccines are prepared: virions are inactivated by treatment with detergent and formaldehyde, a process that destroys the particle. Consequently, the vaccine contains mainly HA and NA and not other components that can help shape a more diverse antibody repertoire. In contrast, it is known that plasmid-based priming can stimulate B cells to produce a more diverse set of antibodies.

The strategy of priming with plasmid DNA followed by boosting with recombinant adenovirus will likely be evaluated in clinical trials for the ability to protect against natural infection with influenza virus. The possibility of a broadly protective influenza virus vaccine that would be taken perhaps every 10-20 years is rapidly becoming a reality.

Wang TT, Tan GS, Hai R, Pica N, Petersen E, Moran TM, & Palese P (2010). Broadly protective monoclonal antibodies against H3 influenza viruses following sequential immunization with different hemagglutinins. PLoS pathogens, 6 (2) PMID: 20195520

Wei CJ, Boyington JC, McTamney PM, Kong WP, Pearce MB, Xu L, Andersen H, Rao S, Tumpey TM, Yang ZY, & Nabel GJ (2010). Induction of broadly neutralizing H1N1 influenza antibodies by vaccination. Science (New York, N.Y.), 329 (5995), 1060-4 PMID: 20647428

Pingback: Tweets that mention Universal influenza vaccines -- Topsy.com

Pingback: Thoughts on this season’s influenza vaccine

Pingback: TWiV 107: Warning – this virus contains email

Pingback: Pandemic influenza vaccine was too late in 2009

Pingback: A $707 million investment in cell-based influenza vaccine

Pingback: Universal Flu Vaccines: Already Here? | The Turbid Plaque

Pingback: Science online, chasing the rainbow edition | Jeremy Yoder