The study subjects were 50 patients with ME/CFS from four sites across the US (meeting 1994 CDC Fukuda and 2003 Canadian consensus criteria) and 50 healthy controls. Some of the ME/CFS patients (21/50) reported a diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome, absent in all the controls. Whether IBS leads to ME/CFS or is a consequence is unclear.

Genomic DNA was extracted from a fecal sample from each patient and subjected to high-throughput sequencing. Bacterial sequences were identified after computational subtraction of human genomic, mitochondrial, and ribosomal sequences.

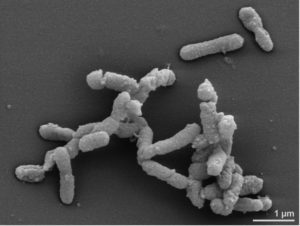

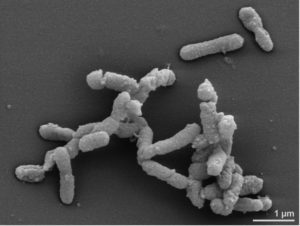

The results show that bacterial taxa in ME/CFS patients with and without IBS were distinct. The most reliable markers of ME/CFS with IBS were increased abundance of Alistipes (pictured) and a decrease in Faecalibacterium genera of bacteria. In contrast, an increase in Bacteriodes and a decrease in Bacteroides vulgatus were associated with ME/CFS without IBS.

The bacterial genes identified in the sequence analysis were used to predict alterations in metabolic pathways. Some pathways are altered only in ME/CFS patients, while others are linked to IBS. Enrichment in the pathway of vitamin B6 biosynthesis appeared to be independent of IBS. This vitamin plays a role in many aspects of metabolism, neurotransmitter synthesis, histamine synthesis, hemoglobin synthesis and function, and more, and is a cofactor for many essential reactions.

The unsaturated fatty acid biosynthesis pathway was also found to be reduced in ME/CFS patients independent of IBS. A reduction of specific fatty acids has been linked to pro-inflammatory responses and immune activation in ME/CFS patients.

These and other metabolic findings in ME/CFS patients validate additional work on bacterial metabolic pathways and the metabolome – the set of small-molecule chemicals – of ME/CFS patients.

Others have previously shown increased levels of cytokines in the plasma and cerebrospinal fluid of ME/CFS patients who had been ill for a short period of time. No such association was found in the current study, perhaps because most subjects had been ill for extended periods of time.

The dysbiosis and bacterial metabolic disturbances identified in this study of ME/CFS patients are intriguing. The results suggest that abundance of certain bacterial taxa could be used as diagnostic markers for the disease. The more important question is whether these changes are a cause or a consequence of ME/CFS. Answering this question is relevant to the potential for using microbiome transplants, or metabolic therapeutic strategies to ameliorate the disease.

Pingback: Intestinal dysbiosis in ME/CFS patients – Virology

There is a rising trend in HK with patients exhibiting similar problems of not having enough bacteria in the intestines which can be a result of severe immunity deficiencies.

Thanks once again for covering ME/CFS science & politics. Greatly appreciated by the patient community. 🙂

Thank you for reporting this and for your support for people with ME/CFS by hosting David Tuller’s excellent blogs.

Correction: IBS = *irritable* vowel syndrome. inflammatory bowel is IBD. 🙂

Pingback: Intestinal dysbiosis in ME/CFS patients – VETMEDICS

Thank you for covering this important and interesting topic. Your support for people with ME is greatly appreciated even by the patients in Denmark.

“The bacterial genes identified in the sequence analysis were used to predict alterations in metabolic pathways.”

I’m sorry if it sounds dumb: but what have genes in bacteria in our faeces got to do with our metabolic pathways? :/

Thank you so much for publishing this and all the information regarding ME/CFS. I am so grateful for your informed coverage.

Gut bacteria produce metabolites which are absorbed into our circulation and used; an example is vitamin K. When specific bacteria are missing, one can look at the genes these bacteria have, what metabolites they would normally produce and what would therefore be missing.

But, as Elio says, this is in the faeces. As I understand it, there are not the absobtive villi in the colon that there are in the small intestine–where the main liquid ferment goes on–, so we need to know what is the bacterial composition in the active part of the gut, rather than in the waste material. I don’t see how we can yet be in a position to make assumptions about our metabolic pathways from looking at genes in faecal bacteria. :/

This is the first step. Next, you can check the plasma of patients to see if the predicted metabolite alterations are observed. If you wanted to get microbial samples from the intestinal wall – an invasive procedure – your study would be very very difficult, if impossible to achieve with the same number of patients.

Pingback: ME/CFS linked to imbalanced microbiome | WAMES (Working for ME in Wales)

I don’t think it needs to be invasive nowadays; and, because the small intestine contents are liquid and constantly being stirred by peristalsis, samples from the ‘lumen’ should be more representative than the dried, compressed, boluses that make up the excreta. Lumen samples could be collected with a modified swallowable camera capsule with ports in the side. A more advanced modification could quite conceivably be made to take biopsies from the gut lining. Wirelessly monitoring these devices en transit, will, I’m sure, eventually give us the variation in microbiome from end to end of the gut, and give us similar ecological information to that obtained from studies of river ecology.

I am just curious if this study can be linked in any way to the study done at Queensland college that proved that the cells of those with ME do not absorb calcium? How might that affect gut bacteria or visa versa?