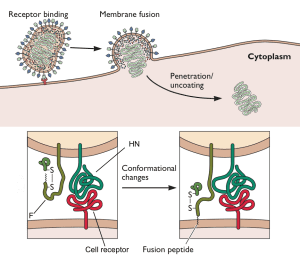

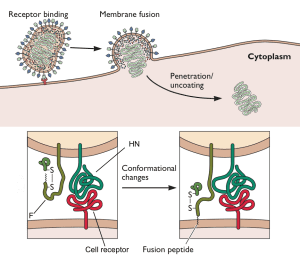

Measles virus particles bind to cell surface receptors via the viral glycoprotein HN (illustrated). Once the viral and cell membranes have been brought together by this receptor-ligand interaction, fusion is induced by a second viral glycoprotein called F, and the viral RNA is released into the cell cytoplasm. The N-terminal 20 amino acids of F protein are highly hydrophobic and form a region called the fusion peptide that inserts into target membranes to initiate fusion. Because F-protein-mediated fusion can occur at neutral pH, it must be controlled, to ensure that virus particles fuse with only the appropriate cell, and to prevent aggregation of newly made virions. The fusion peptide of F is normally hidden, and conformational changes in the protein thrust the it toward the cell membrane (illustrated). These conformational changes in the F protein, which expose the fusion peptide, are thought to occur upon binding of HN protein to its cellular receptor.

During a recent outbreak of measles in South Africa, several AIDS patients died when measles virus entered and replicated in their central nervous systems. Measles virus normally enters via the respiratory route, establishes a viremia (and the characteristic rash) and is cleared within two weeks. The virus is known to enter the brain in up to half of infected patients, but without serious sequelae. The measles inclusion body encephalitis observed in these AIDS patients typically occurs in immunosuppressed individuals several months after infection with measles virus.

Measles virus isolated postmortem from these two individuals had a single amino acid change in the F glycoprotein, from leucine to tryptophan at position 454. This single amino acid change allowed viruses to fuse with cell membranes without having to first bind a cellular receptor via the HN glycoprotein. In other words, the normal mechanism for regulating measles virus fusion – binding a cell receptor – was bypassed in these viruses. This unusual property might have allowed measles virus to spread throughout the central nervous system, causing lethal disease.

How did these mutant viruses arise in the AIDS patients? Because these individuals had impaired immunity as a result of HIV-1 infection, they were not able to clear the virus in the usual two weeks. As a consequence, the virus replicated for several months. During this time, the mutation might have arisen that allowed unregulated fusion of virus and cell, leading to unchecked replication in the brain. Alternatively, the mutation might have been present in virus that infected these individuals, and was selected in the central nervous system.

An interesting question is whether these neurotropic measles viruses can be transmitted by aerosol between hosts – a rather unsettling scenario. Fortunately, we do have a measles virus vaccine that effectively prevents infection, even with these mutant viruses.

I think by the time these patients present with MIBE, the measles virus is not detectable in respiratory tract and so these variants probably do not have the chance to transmit. Thinking is that they arise within the host, particularly in the CNS, and are limited to those tissues. But an experiment with these viruses in respiratory tissue models should be carried out. This could be done easily.

This paper focuses on cell-to-cell fusion but the same machinary controls virion-to-cell fusion. I can’t find growth curves or entry assays on these viruses in this paper but would be informative to see.

I think this work suggests that there may not be a long sought after ‘CNS receptor’ for measles after all.

I wonder what the role of increased fusogenicity (cell-to-cell) is for other neurotropic paramyxoviruses. In particular, mumps, nipah and hendra viruses all have been shown to fuse cell-to-cell efficiently and are all neurotopic/virulent. Experiments with viruses of altered fusogenicity could answer that question.

I apologize if this seems a little uninformed. I tried to do some digging on the web, and couldn’t turn anything up. If the virus is able to fuse with the cell without receptor binding, shouldn’t we see pantropic infection with multi-organ system effects? Or is it the case that the virus becomes pantropic, but remains only immuno and neurovirulent? Perhaps other underlying manifestations have been overlooked or not allowed to develop due to the high severity of the neurovirulent group?

One might consider SSPE to be a serious sequela.