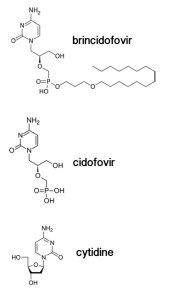

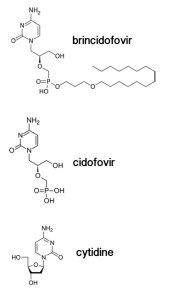

Brincidofovir (illustrated) is a modified version of an antiviral drug called cidofovir, which inhibits replication of a variety of DNA viruses including poxviruses and herpesviruses. When cidofovir enters a cell, two phosphates are added to the compound by a cellular enzyme, producing cidofovir diphosphate. Cidofovir is used by viral DNA polymerases because it looks very much like a normal building block of DNA, cytidine. For reasons that are not known, incorporation of phosphorylated cidofovir causes inefficient viral DNA synthesis. As a result, viral replication is inhibited.

Cidofovir was modified by the addition of a lipid chain to produce brincidofovir. This compound (pictured) is more potent, can be given orally, and does not have kidney toxicity, a problem with cidofovir. When brincidofovir enters a cell, the lipid is removed, giving rise to cidofovir. Brincidofovir inhibits poxviruses, herpesviruses, and adenoviruses, and has been tested in phase 2 and 3 clinical trials. The antiviral drug is being stockpiled by the US for use in the event of a bioterrorism attack with smallpox virus.

Ebola virus is an RNA virus, so why was brincidofovir used to treat the Dallas patient? According to the drug’s manufacturer, Chimerix, with the onset of the Ebola virus outbreak in early 2014, the company provided brincidofovir, and other compounds, to the CDC and NIH to determine if they could inhibit virus replication. Apparently brincidofovir was found to be a potent inhibitor of Ebola virus replication in cell culture. Based on this finding, and the fact that the compound had been tested for safety in humans, the US FDA authorized its emergency use in the Dallas patient.

Unfortunately the Dallas patient passed away on 8 October. Even if he had survived, we would not have known if the compound had any effect. Furthermore, the drug is not without side effects and these might not be tolerated in Ebola virus-infected patients. It seems likely that the drug will also be used if other individuals in the US are infected.

Looking at the compound, one could not predict that it would inhibit Ebola virus, which has an RNA genome. RNA polymerases use different substrates than DNA polymerases – NTPs versus dNTPs. NTPs have two hydroxyls on the ribose sugar, while dNTPs have just one (pictured). The ribose is not present in cidofovir, although several hydroxyls are available for chain extension. I suspect that the company was simply taking a chance on whether any of its antiviral compounds in development, which had gone through clinical trials, would be effective. This procedure is standard in emergency situations, and might financially benefit the company.

Update: The NBC news cameraman is being treated with brincidofovir in Nebraska.

It means that, they are just “testing” by chance if the drug has any effect in the patient..why don´t they use plasma of survivors? The specific Ig of them probably was better option than this drug

Pingback: Dr. Brantly donates blood for Ebola patient, Ashoka Mukpo | Outbreak News Today

They are also going to use plasma of survivors to treat patients. The more different options, the better.

Does anybody have more information, why Ebola virus could be an inhibitor of the viral replication in cell cultures? Possibly even papers?

Thanks in advance! 🙂

Thank you so much for addressing this issue and clarifying some of the technical details! From what I could find on the internet, they just referenced “unpublished data” when saying that it inhibited Ebola cell cultures…

Professor Racaniello, do you have thoughts on whether favipiravir should be tried http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0166354214000576 (given that it is an approved anti-flu drug (polymerase inhibitor) in Japan, is in phase 3 trials in the US, shows efficacy against Ebola in small animal models, and has a large stockpile available? Why is brincidofovir rather than favipiravir chosen for treatment when it looks like its safety and efficacy data is weaker? What in your opinion is the most promising experimental treatment for Ebola–if you suddenly learned that you were infected with Ebola, what would you want to try?

Sorry, i mean […] why brincidofovir could be an […]

Pingback: Treatment of Ebola virus infection with brincid...

It was reported in the media that Thomas Eric Duncan did not get plasma from the US Ebola survivors because none of them matched his blood type. http://www.cnn.com/2014/10/09/health/ebola-duncan-death-cause/index.html

My (by now ancient) work with negative strand viruses and then HIV-1 suggests a very different pathway for treatment. Solutions of cesium salts have been used in the past to combat cachexia in patients with cancer; cachexia is associated with haemorrhagic fever. AIDS used to be called “wasting disease” in Africa early on in the AIDS era because of the cachexia associated with it, thus the term denoted that HIV-1 was sort of a “slow” haemorrhagic fever virus. In contrast, Ebola virus is a very rapidly replicating haemorrhagic fever virus (wihich is what makes it so deadly). As with other negative strand RNA viruses, it is the Ebola nucleocapsid protein that in large part determines the rate of viral replication. I found that the nucleocapsid protein was extremely sensitive to the action of cesium salts (rubidium salts might be even better) while working with VSV and Sendai viruses which, if you look at them as moderately slow haemorrhagic fever viruses, between HIV-1 and Ebola, suggests that the Ebola nucleocapsid protein will also be extremely sensitive to cesium salts and thus that treatment with cesium salts might slow down the rate of Ebola replication to the point that more conventional antivirals and/or the patient’s immune system might have a chance to work before the patient dies of the rapidly increasing haemorrhagic fever.

Benjamin M Blumberg, PhD

there are many survivors in S.African contries! Why did not use one of those!

Pingback: TWiV 306: This Week in Ebolavirus

Couldn’t this enable Ebola to replicate itself into a DNA virus as well, yes we know it’s an RNA virus but it’s high success rate and mutations could be even more lethal?

Could internsl bentonite clay slow down the virus?

I just came across this article on NPR about a Liberian doctor who used another cytidine analog, Lamivudine, to treat his patients. I guess it’s not unheard of for a drug to be effective across different virus families…? I just noticed that cidofovir is really similar to tenofovir, the drug that is supposed to inhibit both HIV and HSV, which I thought was interesting. http://www.npr.org/blogs/goatsandsoda/2014/10/10/355164328/a-liberian-doctor-comes-up-with-his-own-ebola-regimen

Yes, from CDC/NIH. Perhaps we’ll see the data published one day.

It most likely inhibits viral RNA synthesis, as mentioned in the post.

It really depends on how much cesium you need to be inhibitory – you might not achieve such levels in the blood without toxicity.

If brincidofovir inhibits viral DNA synthesis, why doesn’t it affect human DNA synthesis? What makes it target only viral DNA?

I agree 100% with you! Especially when you compare Brincidofovir structure to other treatments in the making like BCX4430 or Lamivudine, which was effective in 13/15 patients Dr. Gorbee Logan treated. Like you said, just looking at the structure of Brincidofovir and taking into consideration the structures of BCX4430 and Lamivudine you could not predict that Brincidofovir would inhibit ebolavirus.

Pingback: This Week in Chemistry – The Smell of Blood, & Ebola Treatment Trials | Compound Interest

Thank you for explaining how this drug could work, and for creating a prominent site for Ebola information.

After reading about brincidofovir and Ebola on the Chimerix web site, it isn’t quite clear to me which level 4 lab tested brincidofovir against an Ebola virus. The test does not appear to have been part of an extensive drug screen.

One lab known for drug screening against Ebola was that of Gene G. Olinger at Fort Detrick. Their capability for screening drugs against what they called “high consequence pathogens” was methodically developed. Here is a paper published when the problem was still being puzzled out. http://omicsonline.org/assessment-of-high-throughput-screening-hts-methods-for%20high-consequence-pathogens-2157-2526.S3-005.pdf

For the U.S. Army and the NIH, the Olinger lab tested FDA-approved drugs in a high throughput screening system designed around a modified (fluorescent) Ebola. According to press accounts more than 2000 approved drugs were screened. The

results were published in June, 2013. The authors were Lisa M. Johansen, Gene

G. Olinger et al. http://stm.sciencemag.org/content/5/190/190ra79.full.pdf

From the 2000-drug screen, only two drugs were singled out for subsequent testing in mice: clomiphene and toremiphene. The drugs block viral entry. Clomiphene injections saved the lives of 90% of the mice infected with a modified Ebola.

Last week, toremiphene was eliminated by the WHO as a candidate for human trials. Clomiphene, which is a cheap generic and a promising prospect, was not mentioned in news stories about the WHO meeting. The pharmacokinetics and delivery of clomiphene, which matter hugely, are discussed and commented upon here:

http://www.pulmcrit.org/2014/08/could-estrogen-receptor-antagonists.html

Since brincidofovir is a new drug, it was probably not included in the Johansen/Olinger drug screen. The 2014 brincidofovir test result, however, could surely have been interleaved with those of the 2000 already-screened drugs, and in this way ranked. Since brincidofovir is one of only two drugs selected by the WHO for human trials, one can assume it performed very well.

Do you mean: would this drug create a selective pressure for Ebola to switch its genome type from RNA to DNA? I don’t know if anyone has any record of a virus doing that, but I’m not sure why one would need to. Each type (DNA vs. RNA, single-stranded vs. double-stranded) has its own advantages and disadvantages — but they are just different pathways to achieve the same end, which is infection. Brincidofovir was made to inhibit DNA viruses, so you’d think that any Ebola, were it even able to miraculously switch genome types, would have an even worse time in the face of such a drug. In any case that would be a really dramatic change to happen so quickly.

It was my understanding that a very small amount of human DNA synthesis is actually inhibited, which is where some of the side effects come from? Or at least that is the case with some antiviral drugs like acyclovir. The issue is always about trying to make the target as specific as possible. I think our polymerases have more error correction mechanisms and are generally more complex. That is a good question.

Pingback: Ebola, Chimeras, and Unexpected Speculation | Limn

Thank you for the info for my project

Pingback: Chimerix Ends Brincidofovir Ebola Trials To Focus On Adenovirus And CMV | PJ Tec - Latest Tech News | PJ Tec - Latest Tech News

Pingback: Chimerix Ends Brincidofovir Ebola Trials To Focus On Adenovirus And CMV « Malaysia Daily News

Dr. Blumberg, thanks for the insights. Very helpful understanding the progress on these products