Recently three cases of confirmed infection with 2009 influenza H1N1 were reported in Chile. The first patient had laboratory confirmed infection; treatment with oseltamivir resolved symptoms after 48 hours. Twenty days later the patient developed a second bout of laboratory confirmed influenza which was treated with amantadine. The second patient acquired laboratory confirmed influenza in hospital, was treated with oseltamivir and recovered. Two weeks later, while still in hospital, the patient had a new episode of laboratory confirmed influenza infection. Treatment with oseltamivir again resolved the infection. The third patient also acquired laboratory infection in hospital, was successfully treated with oseltamivir, and was discharged. He was readmitted 18 days later with confirmed pandemic H1N1 2009, and again successfully treated with oseltamivir.

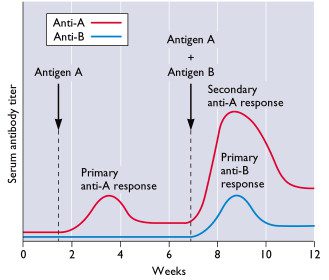

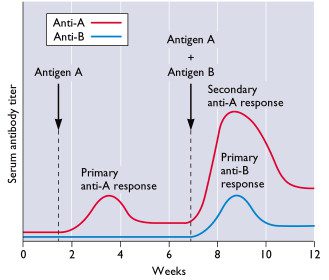

These individuals were likely resusceptible to reinfection with the same strain of influenza virus due to a confluence of unusual events. First, all three were reinfected within three weeks, before their primary adaptive response had sufficiently matured. Another contributing factor was the high level of circulation of the pandemic strain. This issue was compounded for patients two and three who probably acquired both infections while in the hospital (called nosocomial transmission).

Could reinfection also occur after immunization with influenza vaccine? Yes, if the immunized individual encounters the virus before the primary antibody response matures, which occurs in 3-4 weeks. This is more likely to occur during pandemic influenza when circulation of the virus is more extensive than in non-pandemic years.

Perez CM, Ferres M, & Labarca JA (2010). Pandemic (H1N1) 2009 Reinfection, Chile. Emerging infectious diseases, 16 (1), 156-7 PMID: 20031070

Very interesting. Did the fact that these patients all received early anti-viral treatment have something to do with their secondary immune response being incomplete ?

I meant to say “secondary antibody response”.

Pingback: Tweets that mention Reinfection with 2009 influenza H1N1 -- Topsy.com

Pingback: Reinfection with 2009 influenza H1N1 | Attention to health

Pingback: Reinfection with 2009 influenza H1N1 | H1N1INFLUENZAVIRUS.US

So when is a person protected against the virus after vaccination? After the primary antibody response is complete or when the antibody titer reaches at least 1:40?

Did anyone look at their antibody titers? It would be interesting to know if, a couple months later, they had enough neutralizing antibody to stop the infection a second time.

Has anyone assessed whether those recently prescribed oseltmivir are more likely to transmit HINI to non-carriers/vaccinated individuals?

If there is a latent period between vaccination and the onset of mature antibody response, then what are the markers used to define 'mature'?

Fascinating… more questions than answers?

so, how much do you estimate does vaccination reduce the probability to get it ?

50% ?

Wouldn't almost anything that decreased virus levels in your body (like Tamiflu) make you *less* contagious, instead of more?

Along with Margaret, I wonder if treating them with Tamiflu had anything to do with the reinfection. But there's a sampling problem here–having a lab-confirmed case of swine flu probably makes you way, way more likely to get Tamiflu, and without that “lab-confirmed” part, I guess everyone would assume you'd just had two separate nasty respiratory illnesses, maybe two different strains of the flu.

Perhaps we need to be careful here. Decreased viral levels may also mean suppression of the immune response and that in itself is surely undesirable in both the long and short term? There is a tendency when measuring the effects of medical intervention to ignore the natural immune response which is attempting resolution or homeostasis. If dampening the normal and healthy reaction to infection are you not actually creating further problems inadvertently

I don't mean to digress too far but the same thinking suggests NSAID's are a useful Tx for inflammatory conditions such as the athropathies, but there is evidence to suggest that as well as creating GI upsets due to Cox 1/2 related damage, you are stopping the immune function dealing with the current problem adequately, and slowing natural resolution.

We need to consider the individuals innate immune response, viewed from their clinical history (and perhaps genetic profile?), before jumping to the conclusion that the short term reduction in symptoms is in the patient's best interest.

Still interested in establishing the markers used to define 'mature'…. anyone come up with some suggestions?

Surely natural immunity varies greatly within the population and is subject to so many unquantifiable factors to make a guestimate entirely unsupportable.

Biological individuality is the rule not the exception….

thank you.

You seem to have not considered an alternative hypothesis: tthat treatment with oseltamivir (Tamiflu) was either incomplete or otherwise ineffective in these pateients. This explanation alone, I suggest, would be sufficient to explain the redevelopment of patent disease in these pateients. Indeed, given the clear past evidence of spread of Tamiflu resistance swine H1N1 (acknowledged by the WHO on occasions then strangely removed from the record in more recent communications), and, as is likely, widespread nature of these viruses albeit as minor species in mixed populations, and, when one also takes into account the indisputable fact of global spread of Tamiflu resistant human H1N1 during 2007-08 (in which non-resistant human H1N1 viruses were almost completely displaced by the resitant strains) – i'm surprised this wasn't the first possibility that you would raise. Perhaps it's my epidemiological bent.

But there was something else I wanted to take issue with you on. I noted comments of yours some days ago on the FluTrackers.com site in which you appear to be advising that stocks of flu-antivirals ought to be reserved for persons with underling illness – not used for the benefit of the wider population. I think I recall you suggested this was best until more types of antivirals were available to allow a regimen-based treatment (as is usual for HIV management).

The problem with this idea, of course, is that were a sufficiently novel, highly transmissible, highly virulent (ie. lethal) flu strain to appear and trigger a subsequent pandemic wave not well matched to the available vaccine, on the scale, for example, of the 'Spanish flu' event, your proposal would condemn some millions of otherwise healthy people to an unpleasant death. Would it not? Surely, much better that stockpiles of life-saving antivirals (especially those that that still retaining widespread efficacy (ie. those to which known flu strains haven't developed large scale resistance to) – are available in suffiicent quantity to treat all who become infected – even given the present lack of other antiviral classes. Surely, that's the objective of having sufficient antiviral stocks to save lives and mitigate injury. Bear in mind, in 2009 20%-40% of swine flu mortalities were otherwise healthy adults (depending on country) according to the last statistics I remember (though some months ago).

Three cheers for big pharma! Pharmaceutical companies big enough to develop, test and mass produce these life-saving medicines. Such are the benefits of science, capital, markets and the profit motive.

'But there was something else I wanted to take issue with you on. I noted comments of yours some days ago on the FluTrackers.com site in which you appear to be advising that stocks of flu-antivirals ought to be reserved for persons with underling illness – not used for the benefit of the wider population. I think I recall you suggested this was best until more types of antivirals were available to allow a regimen-based treatment (as is usual for HIV management)'.

To whom were you referring when you posted this?

Could it be that the banksters-cum-sociliasts – who have stolen future cash through debt indenture – have left little for population-scale life-saving drugs with a decent shelf-life? Perhaps that is what those gamers mean in their criticism of pandemic-related expenditures???

The author of the heading piece – Vincent of course. Whilst I don't have the link to the FluTracker article mentioned – it was certainly attributed to him.

That should read 'FluTrackers.com' site. Freudian slip.

Mmmm. Host-derived markers to enable assessment of clinical susceptibility to influenza infection (which is, if I understand correctly, what you are suggesting?) is very likely to prove a virological 'wild goose chase' is it not? The rate of genetic mutation and the rate of spread of favourable genetic changes among the wider flu virus population (“quasi-species complex”) will I think render such a programme akin the a virological 'wild goose chase'.

Further to my comments above, I draw your attentions to the 1998 paper by Domingo et. al.: 'Quasispecies structure and persistence of RNA viruses' – which can be accessed freely at:

http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/eid/vol4no4/domingo.htm

and provides, I think, a aprescient understanding of the co-evolutionary population dynamics of host-parasite interactions that I believe provides the key theoretical underpinning for the future management of highly dynamic RNA viral diseases such as influenza.

Further to my comments above, I draw your attentions to the 1998 paper by Domingo et. al.: 'Quasispecies structure and persistence of RNA viruses' – which can be accessed freely at:

http://www.cdc.gov/ncidod/eid/vol4no4/domingo.htm

and provides, I think, a aprescient understanding of the co-evolutionary population dynamics of host-parasite interactions that I believe provides the key theoretical underpinning for the future management of highly dynamic RNA viral diseases such as influenza.